State of Belief

"Curiosity, Not Contempt": Adam Nicholas Phillips on Bridging Divides

What does it mean to build bridges amidst the turmoil of the second Trump Administration? How have interfaith communities moved forward with productive dialogue post-October 7th? Is there a more nuanced way to think about Christian Nationalism and the MAGA constituency? In this episode of The State of Belief, Rev. Paul Brandeis Raushenush and Interfaith America CEO Rev. Adam Nicholas Phillips explore these critical issues and much more. Adam's personal journey into interfaith work is compelling. He describes his upbringing in a non-traditional religious environment, his exploration of various faiths, and his eventual identification with evangelical Christianity. His experiences, including planting a church and getting through the consequences of advocating for LGBTQI+ inclusion, have shaped his understanding of faith and public life.

Listen for an in-depth look at:

• Interfaith America’s work on managing conflict in classrooms and workplaces, creating opportunities for groups to move beyond just coexisting and rather collaborating for a common cause.

• How the inspiration of Live Aid and Adam’s past experience in leadership at USAID during the Biden-Harris administration, as well as as a faith leader, inform his current position as CEO at Interfaith America.

• Navigating our polarized environment: “We find ourselves at a crossroads of sorts where the politicization of a number of our traditions has become quite difficult and untenable. But I keep trying to come at this with some sense of curiosity and not contempt.”

Where to find Adam:

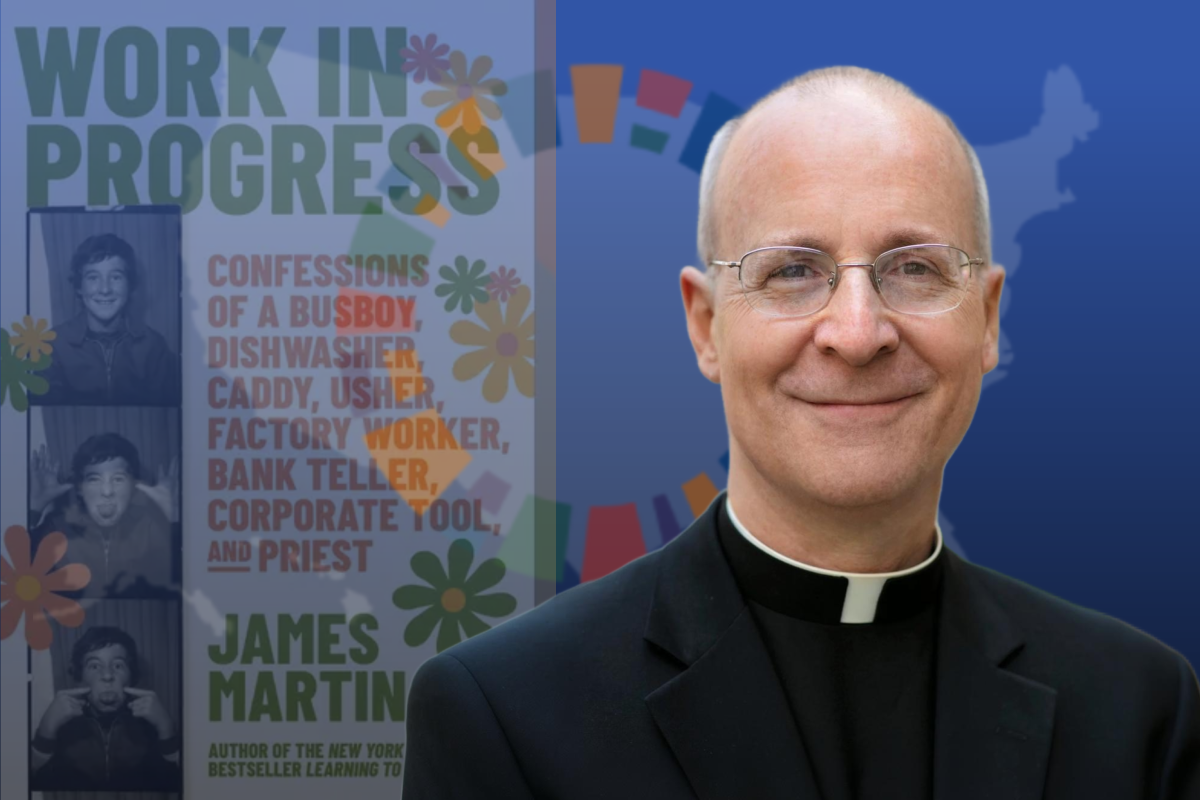

• Check out his book, Love, Light, Joy & Justice: How To Be A Christian Now

• Embrace the “power of pluralism,” and get involved with Interfaith America.

• Hear more from Adam in his Ted Talk, “Inclusion: the ancient idea that just might save all of us.”

There’s a lot to learn from this conversation. I hope you’ll share it with someone you know who’ll enjoy hearing it!

Transcript

REV. PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH, HOST:

Rev. Adam Nicholas Phillips is the Chief Executive Officer of Interfaith America, where he leads strategic operations to promote religious pluralism and civic engagement. Adam previously directed the Center for Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships at USAID, playing a key part in interfaith diplomacy and global development initiatives under the Biden-Harris Administration. He also co-founded Christ Church: Portland, an inclusive, faith-driven community. So Adam brings a unique combination of activism and spiritual leadership across religious and civic spaces to this moment in America, and I am so very happy to welcome him to The State of Belief.

Welcome, Adam!

REV. ADAM NICHOLAS PHILLIPS, GUEST:

Paul, it's so good to be here. Thanks for having me.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

So you are at Interfaith America, my old stomping grounds, and I am very excited that you are there. And what a moment. We’ve said that our democracy needs both Interfaith Alliance and Interfaith America, and so why don’t you say a little bit right off the start about what’s going on at Interfaith America right now that you would love for our listeners to know about and, potentially, participate in?

ADAM PHILLIPS:

Yeah, Interfaith America, founded by our friend Eboo Patel, founder and president. Started this organization 24, 25 years ago, in a house with friends with this sense of purpose around interfaith belonging and a new need for a different approach to interfaith dialogue more akin to understanding and bridge-building for a common cause - so service in the world. And then it evolved into an organization that was rallying youth - we used to be called Interfaith Youth Corps - rallying high school students, but then college students, on campuses across the US. It's had a number of different iterations, but in 2022 was rebranded as Interfaith America. I know you worked on that rebrand. So we have two IAs on this…

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

That’s right. That was one of my big claim to fame at the time, bringing Interfaith Youth Corps into Interfaith America. And now I haave to keep correcting myself, and I give a big fee to Interfaith Alliance every time I refer to us as “Interfaith America.” But I’ve got it now.

ADAM PHILLIPS:

I’ve been a friend and fan of Interfaith Youth Corps and Interfaith America for a long time. I met Eboo at a coffee shop on the north side of Chicago, here, when I was pastoring a small neighborhood church, and we struck up one of those friendships where you stay in touch over the years. Touch base, you know, every couple years or a couple times a year, maybe grab a coffee when you're in town in D.C. or Chicago.

But with the rebrand in 2022 - I was serving in the Biden administration at USAID - I attended that announcement at Georgetown University, and really exciting to see IA evolve and step into this sense of purpose around bridge-building, civic pluralism for the common good across a number of program areas. Higher ed is our first and founding practice, but we are increasingly engaged in workplace diversity trainings, health care, and civic engagement. And that’s what drew me to this opportunity to come and join the team.

And this past March, Eboo and the board appointed me as the organization's first ever CEO. And so Eboo is founder and president, and he's currently working on a really exciting book on pluralism that we're all eager to see, and he's doing some speaking, and he's very much still part of the organization. But I'm running the day-to-day operations, helping lead the strategy. And I wouldn't be able to do that without the amazing team of folks that you worked with on the executive team and then across the organization.

I will say this, since I've been here, now almost two years, we have nearly doubled in size. And our phone is ringing in terms of the great need out there for bridge-building and trying to figure out ways to cooperate across our vast differences, whether they be faith or or other identities that we all hold.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

You know, one of the things that obviously has really gripped and actually rended, I would say, the nation was what happened in Israel on October 7th, and then the aftermath. And certainly, a group that really focuses on university campuses must have been very engaged, aware, trying to imagine a path forward.

How are you thinking about what is happening on college campuses? Antisemitism, but also balancing that with freedom of expression, understanding academic freedom. I mean, these are some major principles and cornerstones, all of them, of a democracy, including combating antisemitism. How are you working with all kinds of people, I'm sure, imagining a way forward?

ADAM PHILLIPS:

I think about October 7th quite a bit. It was my first week on the job here at Interfaith America. I actually, before I accepted the role, I was set to be in the West Bank in early October in my capacity as a diplomat and development leader for USAID. That was a long-planned trip. So I'd been thinking about Israel and Palestine all throughout that year, in terms of preparing for that trip. It got taken down a couple times because of the protests in Israel around the court cases, etc, etc.

So this tremendous horrific outbreak of violence and destruction that is happening in this small corner of the world, it's probably one of the most profoundly interfaith moments - not just for that part of the world, but for our country too. I have friends who have family that have suffered immensely on both sides of the conflict and on no side of the conflict, just caught up in the violence and the desperation of decades-long pursuits for peace and for understanding; and ideally, some of us would say, for a two-state solution. So that's where I was thinking about when I woke up to that news on that morning, on October 7th.

For Interfaith America, we've been solely focused on US matters. We've tried to really respectfully not speak into global issues for some time. Now, I'm a global development practitioner, so I have concerns around what's going on, not just in the Middle East, but in other parts of the world where you have aspects of hunger, war, on and on. That moment, though, for the organization, was a really important one for us to think about: how do we show up with the best of our ability and a sense of purpose and service to help folks bridge-build despite the immense opinions and differences?

I mean, first of all, the horrific attacks on the day of October 7th. Again, I have friends that had lost loved ones on that day. What a tragic series of images out of that music festival where you have young people that - you talked about freedom, just the freedom of expression and belonging - and then the immense waves of violence that have continued to this day in Gaza. So I weep when I think about what's happening there.

I was actually supposed to be in Israel again this summer, and then that got taken down because of the military action with Iran. So it's interesting. I'm so far removed from that part of the world here in Chicago. We are focused entirely, as you were talking about, on college campuses and workplaces and in civic spaces. And yet you can't avoid this conflict in American public life. So we're trying our level best to show up with partners, with students.

We have a big student conference coming up in a few days' time here. Over 700 attendees at our summit. And it's really a forum for us to help provide some tools and some learning - and for us to learn as well - what's going on on college campuses and elsewhere in American life.

You know, since October 8th, as we said, our phone and emails have been just inundated with requests to come and help. That goes from top to bottom in the organization. We've worked across a myriad of very elite higher ed institutions, university campuses. We've been brought in to help with some workplace challenges, as you can imagine, in the cubicle or at the water cooler, or even in the surgical ward - you've got folks that need to figure out how to work together despite their different opinions on these matters, and we've been brought in to help do some of that work, which I'm really proud of.

And then in the civic space, we've got a number of really exciting and encouraging opportunities to work with folks from all walks of life - a number of different religious traditions that are reflecting on the conflict in the Middle East, but also reflecting on the conflicts that seem to be unfolding in our own country. And we're having a robust series of conversations on religious liberty, how do we work together despite tremendous doctrinal differences for sure; but also, how do you see the other side of that coin? How do we not just coexist and work together, but how do we work together for a common cause to face the challenges of the day, no matter our party, no matter our religion?

And that gives me hope, because I see, despite tremendous violence, despite tremendous unrest in what Amanda Ripley calls high conflict, we see folks coming from right, left, a myriad of religious expressions and traditions, trying to be forward-leaning and trying to be problem-solvers in spite of all these challenges.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

It's a tough time. And I think that there's a big role for Interfaith America to play - if people want to play, that's another question.

I do want to step back a little bit and talk about your origin story, because everybody has a story how they get into interfaith work, and they're all different. What was the tradition you were raised in? I had an impression that you were raised more in the evangelical tradition, but I might be wrong about that. What's your background, and how did you get from there to here?

ADAM PHILLIPS:

Yeah, it's a funny story, actually. I didn't really grow up with any particular religious tradition. I had parents that were rooted in various Christian traditions, but thinking about ways to raise me and my sister up in a way that was maybe allowing us to choose.

And so I grew up watching MTV, and Live Aid was very important to me. As a very young child, I often joke that MTV was our babysitter. Back before we had Netflix Kids and Disney Channel and all the things and babysitters. But Live Aid was really important to me, because I got to see at a very early age people from all walks of life coming together for a crisis, which was the famine in Ethiopia. And that really set me on a trajectory to kind of think about the world outside my small Ohio neighborhood.

We ended up moving to California, and I grew up just looking for ways to belong and trying to find something maybe more rooted and ancient. I wouldn't have called it that when I was, you know, 10, 11, 12, but looking for something beyond the kind of suburban experience I had. And I ended up going to church with whoever would take me in San Diego. And I went to Catholic Mass, where I heard sermons on social justice and the Eucharist and sort of the saints, you know, St. Francis. I ended up going to pretty interesting kind of mainline progressive churches; a number of boring churches. But one of my best friends took me to his very charismatic evangelical youth group, and that was a place where I first heard the scriptures in a way that came to life for me.

So I ended up going to college and started looking for college ministries to kind of go deeper in my own personal journey, ended up at the Navigators, and I became an evangelical for the better part of a decade. And I really still identify deeply with some of the markings of what it means to be an evangelical, the urgency of mission and the sense of the scriptures being alive, even for us today, and the ongoing presence of the Holy Spirit.

It's a longer story, but I ended up planting a church years, years, years later in Portland, Christ Church, and got caught up in some of the culture wars that we're still dealing with. I got asked to leave my denomination around our commitment to marriage equality and full inclusion of LGBTQIA.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

What year was that?

ADAM PHILLIPS:

It was 10 years ago. And, you know, our story was picked up by the AP, HuffPo, Washington Post. And we were really, I think - I didn't know it at the time, but on the vanguard of an evangelical movement that was looking to kind of broaden the invitation for folks - and not just the invitation, but the table, for folks to come and be part fully, whether you're straight, gay, or whatnot. So that was 10 years ago. And I see shadows of what was going on in that time in 2015 that we're still reckoning with today when it comes to faith and public life.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Yeah, it's interesting. I love that Live Aid was almost the launch of your journey. That's so beautiful. And it actually makes sense that you went to USAID. There's a connection there, something bigger than myself, and that I had a purpose, and that it mattered what I did and how I showed up. to the well-being of others that, again, in turn, allowed me to be well. And I think that's a very beautiful story. It definitely preaches.

But also, I would say one of the you know, phenomenons that you're a part of is like some people got really, you know, they sense the power and the commitment of the evangelical tradition and the language and it matters what you do. It matters how you show up. And that is very attractive, I think, to anyone. Certainly, I understand it, although I'm not from that tradition.

But then you have this moment over the last 10 years and starting even a little bit earlier where evangelicals like yourself who had the Live Aid start and didn't go into it for the culture war kind of idea have begun to become a different phenomenon, whether it's ex-vangelicals or whatever, all these people have almost like the purity test. Now it's almost impossible to call yourself an evangelical and be pro-marriage equality. People will just be like, nope, you're out of the club. So my guess is that you still wrestle with who's in, who's out, who gets to claim the mantle - because that's always a big thing.

A commie like me, I was raised in the mainline church. I've been from the beginning automatically out. Someone like you, where you fit in the fold - and this is, by the way, not just Christianity or evangelicalism within Christianity; every religious tradition has this, well, oh, you don't count, you're not real, you know.

One of the things I'm very interested right now is just talking about my own tradition and reclaiming that, actually, I do come from a tradition. It's not just a pale like yours. I come from a tradition that made some decisions and has a vantage point and leaning into that, and I think that part of my way into that was through the interfaith conversations where, when I was at Princeton heading interfaith conversations, the conversations were such that it kind of made everyone really come to grips with, well, what do I really believe? And where does it come from?

And I think that's one of the advantages of an Interfaith America, is the invitation to go deep into your own tradition and own it and show up with it in conversation with others, in dialogue with others, and without a sense of: it's my way or the highway. You can believe that your way is right. but it doesn't have to preclude the existence of others. And I think we are, right now, in a moment where some of the hardest core of the tradition you came out of do really feel like they want to claim religion for America.

How do you deal with what some refer to as Christian Nationalism, White Christian Nationalism? Is that part of your lexicon at Interfaith America? Or do you prefer to imagine that everyone can have a conversation about religion and figure out a way forward together?

ADAM PHILLIPS:

That's such an important question - and one that I think takes some time to unspool. So I'll get to the religious, the Christian Nationalism piece in a moment. I mean, ever since the Charlottesville incident with the tiki torches, I've been thinking about the impact on American life on that day.

You mentioned my time at USAID and Live Aid. There was a tandem moment in the Live Aid story, which is Live 8, which was Bon,o U2, and Bob Geldof and the McPoverty History Movement that I was part of. I actually was working at the One Campaign, Bono's organization that he started with friends. And I often talked about, growing up, that my spirituality was rooted in a handful of U2 CDs and the World Vision kid on the fridge. So this idea of music that touched you in meaningfully personal ways, but also profound, like a global call to action. And then this image of God that's on your fridge, this child that needs help.

I ended up working with World Vision for a bit. And when you think about evangelicalism, you think about - it's a misnomer to say it's a monolithic tradition. It's a myriad of traditions. There was a movement called the Micah Movement, which was coming up from the Global South. You've got folks from Australia and the UK and Canada that have differences of opinions on what White evangelicalism looks like, and even a pluralist evangelicalism looks like. The Lausanne Movement, which I was part of that, as well. So it's very fascinating.

I still read Christianity Today. We work closely with folks from evangelical communities, people that are working on racial justice, people that are working on climate change. But we find ourselves at a crossroads of sorts where the politicization of a number of our traditions has become quite difficult and untenable. But I keep trying to come at this with some sense of curiosity and not contempt, Ezra Klein talked about that. That really resonated with me out of my own spiritual work and the teaching of Father Richard Rohr and the Center for Action and Contemplation when I got booted from my denomination.

I still have loads of friends from that tribe. But when I was exited from that denomination, I had some friends that sent me to see Father Richard and Rob Bell at a two-day retreat. And that's when I started to have this glimmer of hope that my faith could be put back together again, and that there was this sense of lineage to a tradition that was bigger than 1950s America, even deeper through the social gospel movement, which I know you know well, going back to really ancient rooted ways.

And Father Richard often talks about being on the edge of the inside. And so I try to see myself as on the edge of the inside, as a bridge builder. John Ward wrote this really interesting book, and he talks about border stalkers and this notion of folks that I think he's quoting from, I forget his name, but this notion of border stalkers are folks that know how to transcend borders, but not leave their own traditions.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Yeah. John was at Huffington Post when I was there. And he wrote a really interesting memoir book, and I was so moved by that book. In fact, he came on this show and spoke very movingly about that book. So I love all the people that you're referencing, because here's the great thing about that, Father Rohr and Rob Bell and John Ward, all these people are those border people. And I'm never going to be in the evangelical community, but in some ways, many of those folks, Shane Claiborne and others who are in that nexus have been really informative for me.

And Father Rohr is such a national treasure, and grateful for all that he is, all that he offers. So I appreciate this ongoing willingness to be in that border crossing role. I think that's really good for you, and really good for Interfaith America to have you there.

ADAM PHILLIPS:

I feel very humbled by the weight of the work. The term “border stalker” John got from Makoto Fujimura's book Culture Care. And it's just this beautiful notion of: you don't have to leave your tradition. In fact, the best way in order to be a bridge-builder or to be a border stalker is to root deeply down in your tradition.

And you brought up Christian Nationalism earlier: I was at a gathering in February of this year, and it was a number of very good friends and usual kind of partners all talking about White Christian Nationalism and I said, yes, I agree that there is a concern around White Christian Nationalism. You see this in the weaponization of social media algorithms. You see this in alternative Christian media. You see a long lineage going back pre-Civil War of some deeply troubled White Christian issues when it comes to race, when it comes to a whole host of ideas around what the nation is.

And yet, I think we've got to figure out another way of threading the needle on that conversation, because I could talk about, as I just did, a whole host of evangelical friends and neighbors that would bristle at that. And I think we lose people when we just kind of overstate the issue. And also, when you look at the past election, you had a multi-racial, multi-religious, multi-ethnic coalition of voters that voted for President Trump to go back into office. And so it's very complicated. We live in a very complicated, interesting, and at times very troubling time.

So I think we've got to figure out new ways to navigate and name the issues so that we can get not out of this process, but through it - and ideally to a place on the other side, America, 250 years old next year, a place that's really delivering on the dream that King and others, Fannie Lou Hamer and others called us to dream.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

I'll push back a little, but that's my job.

ADAM PHILLIPS:

Please.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

And you have your job. But the way this administration has approached religion is not multiracial, multicultural. The Religious Freedom Commission that they have put forward entirely consists of very right wing Christians, one. They've attacked the Catholics, they've attacked the Lutherans, they've attacked everybody who isn't in lockstep with their position. And the Anti-Christian Task Force is just a means to suppress other…

This is my perspective, but I do think that if you actually look at the way this administration and the people they've surrounded themselves with as far as religious advisors, these things are not like any other administration. It's not like the Bush administration. This is a very particular moment that we have to reckon with. And I think we have to be real about the threat.

But what I like about what you said is that I do think that there are the hardcore MAGA Christians, which is, I think, one way of thinking of it. And then there's lots of people around them who are trying to live out their faith, who can be part of a broader coalition to move America forward that is truly diverse and not privileging White Christians, because I think that is actually one of the underpinnings of Project 2025 and others. And I know you're not disagreeing with that, but you also, the way we approach that at Interfaith Alliance and the way you approach it at Interfaith America have to be different. And we're so grateful for that breadth of strategy. And this is an ongoing conversation.

ADAM PHILLIPS:

I hear what you're saying. I do want to touch on that. I think when you look at the electorate, when you look at November 2024, you saw something that I don't think folks, certainly from the party that I come from, were thinking about when it comes to race, religion, ethnicity. There was a coalition of voters that reflected the broad swath of the whole country, which in some ways, you could say, is a very exciting and promising thing.

On the other hand, what you described in terms of the administration's approaches on some of these things, they are quite mystifying, I'll admit, because they do reflect not the entirety of their own electorate. I worked in the Biden-Harris administration and inherited a portfolio at USAID from the Trump I administration. And I was brought in to serve day one to figure out the portfolio, the international development and aid portfolio, the religious liberty portfolio. They were also super critical to the Biden administration. And I ended up advancing much of Trump I policies because they were really great.

And Trump, that's the thing about aid and development and these coalitions, you know, you have this notion that something in Trump I is different than Trump II. And so, yes, I think there's a proud tradition of bipartisanship or nonpartisanship, even, in the so-called White House Center for Faith-Based and Neighborhood Priorities. It's changed its name depending on the administration. But I would regularly call Bush officials to be like, how did you navigate this? How did you figure out this? As well as Obama officials who I was working with in the Biden administration, and Trump I officials as well. So something's different here in Trump II. I've got friends that are in the administration. I'm cheering them on. I'm also concerned about the sense that we need people to unite us rather than continue to divide us. And as much as we can be useful in conversations around finding a third way approach, I'm absolutely here for.

But curious, how do you all approach that at Interfaith Alliance? I know we have different missions and approaches and we're trying to learn.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

We're very interested in building the coalitions that can continue to move the country forward with true religious freedom and true diversity. And of course, our commitments extend to civil rights. So religious freedom in concert with civil rights. So what does it mean to support the idea that someone can withhold a service to a gay person? This religious liberty claim abrogated the civil rights of a person just to have public accommodation. And really recognizing that there's a power flex right now that is there. I mean, the people who are in power religiously are overt about it.

I just had a guest on. He was like, the goal for us is to have White Protestant as the norm. And everyone else is allowed to be here. But they're allowed to be here. They're not the center. They are not essentially the culture. And that feels to me like not only a terrible world in which that person gets to decide who is the center, but also a total refutation of the First Amendment and what it means to have a Non-establishment Clause, as well as a freedom of religious expression. So we're very concerned with the flex right now, and how it's just showing up.

For instance we're very concerned about the effort to put a particular prayer in public schools; were concerned about Ten Commandments in schools. And evangelical chaplains in public schools replacing college counselors and what that would mean for people from no faith tradition, minority faith traditions, or a queer kid who's like, I'm trying to figure something out. And you have, instead of a school counselor, a volunteer evangelical chaplain who has no restrictions on proselytizing.

ADAM PHILLIPS:

Yeah.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

So I think that we are focused more on what are the implications for the policy and the future of America and the way we live together. And we build bridges in order to bring people together to kind of recognize that maybe that's a need that we all need to go all in on together. And really trying to build - and sometimes rebuild - coalitions of people who stopped talking to each other post-October 7th, but actually really want to talk to each other, and finding ways to show up for each other in policy discussions in this moment.

So, we are a bridge-building organization in order for policies to reflect the broader public. Our founding was specifically to counteract the Christian Coalition. At our founding, we were political. We're still political. We're not partisan, but we're political.

I think it's so important that we talk about the experience, the personal experience for you of watching what happened to USAID, and maybe you can give us a little bit of an update. But I have to say, those early days, it just felt like the heartbreak of losing the Department of Education, losing USAID. And what was behind all of that?

It wasn't budget. It wasn't saving money. I'm sorry. Or maybe there was… It felt like more of, we are going to destroy these elements of what the government is. Because, you know, if you can pay 200 million to build a gaudy ballroom - can you imagine how terrible that's going to be in the White House - you can keep keep some programs afloat. So talk about your own experience at USAID. You've mentioned it and it sounds just so fulfilling and kind of on your own trajectory from Live Aid. But what's going on at USAID now? And what can we know? What can we learn?

ADAM PHILLIPS:

USAID was started by President John F. Kennedy as, really, learning from the Marshall Plan. In fact, the first logo of USAID is lifted from the logo from the Marshall Plan, this really incredible image of a U.S. kind of seal with two hands shaking despite the aftermath of World War II and the division that was underway with the Cold War and the starvation of folks in Berlin. So, you know, Kennedy's seeing all this and thinks to himself, with the threats of communism abroad in Vietnam and South America and elsewhere, that beyond just sort of normal, quote unquote, “foreign policy approaches” through the Pentagon or through the State Department, we needed something that really illustrated the heart and soul of American values.

And of course, throughout 60 years of history, you've got stories of waste, fraud, and abuse. You've got stories of challenges. We knew some of those in the Biden administration, things that were left undone from the Trump administration. I'm sure the Trump folks saw some that were left undone from Obama. So it's complicated when you look at reform. And every administration has looked at reforming government. That's the right of every president; policy matters, and that's why elections matter. And we were working to do our own version of reform when I was at USAID.

I got invited to work at USAID in the administration, or at least invited to go through the process, after working on the 2020 presidential campaign. I had never thought about really working in government, I'd always seen myself as somebody that was on the outside influencing policy or government through advocacy. For me, part of my own spiritual tradition is using my voice to impact public policy for the common good. I've done that through hunger, with Bread for the World. And I did that at the One Campaign, working on HIV AIDS, child and maternal health, the Millennium Development Goals at the time, climate change.

And I was always, I mean, at Bread and at One, these are like immensely, strongly rooted bipartisan advocacy organizations. And so through that time, I was regularly meeting with then-Senator Rubio's office, meeting regularly with Senator Graham's office. And it was really the kind of, the compassionate conservatism, if you will, of the Bush years that were deeply committed to these values of making this sort of Kennedy idea around foreign aid even more compassionate, even better.

And so when you think about the AIDS crisis and the president's emergency plan for AIDS relief, started by George W. Bush, carried forward by Obama, Trump I, Biden, it seems like it's still maybe going to survive some of these cuts. You look at this lineage of strong, deeply rooted American bipartisan solutions to foreign aid and assistance. I got to work on that.

I had a global portfolio, not just advising on faith-based initiatives, but working closely with Ambassador Samantha Power and colleagues on localization efforts. How do we move more money and support to local entities, neighborhood partners, if you will? How do you move decision-making to those partners? And this was incredibly challenging, bureaucratic, efforts. And so our reform work was to do burden-busting. How do we make it easier to work with that women's co-op in Guatemala, or that LGBT group in Kenya? How do you make it easier to not just import ideas from the states, but work closely with people on the ground?

And USAID has this immense network of non-political - you're talking 10,000 plus employees, dedicated development practitioners, folks that are part of the Civil Service or the Foreign Service, and would work with whatever administration came in.

So what happened in February of 2025 was heart-rending, absolutely shocking. I think I wrote about it at the time in RNS, Religion News Service, but the best of America's bipartisan global witness was being dismantled in front of our very eyes. Every administration has the right and power to rethink policy, to change up some things. But what happened with USAID in February was the decapitation of the agency's expertise and workforce. I think it's whittled down now to, maybe… I don't know the numbers, it was all moved to State. I think it's somewhere in the 1500 range of employees. They are now working on an America-first aid policy. Which, again, is their prerogative.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

What does that mean?

ADAM PHILLIPS:

I don't think we know entirely what it means. I've been told that it means a commitment, still, to immediate assistance after earthquakes and tsunamis where American dollars can flow in and provide some help. I think it continues to mean PEPFAR; AIDS relief was not just about doing the right thing for folks that were living with AIDS, but it was about ensuring that countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, were not seeing their economies hollowed out, not seeing sort of violence raise up amidst those economic challenges. So it was also a shrewd, smart America First policy around not just foreign assistance, but international security. So I think some of it still will remain.

But when you wipe out close to 10,000 employees and then since shockwaves like a tsunami throughout the development sector: World Vision's laid off - I don't even know how many, hundreds if not thousands; Catholic Relief Services laid off hundreds if not thousands; World Relief... And then a whole host of secular organizations.

What folks don't realize about USAID is that it's worked with faith-based groups for 20, 30, 40 years. And two of its largest partners - not faith-based partners, but just two of its largest partners in general - Catholic Relief Services, World Vision, that are doing things deeply rooted in their own traditions, navigating US policy, but doing it out of their own traditions. It's devastating and it puts lives at risk. It's certainly threatened the livelihoods of friends of mine, but I think most importantly around the child that will not have access to RUTFs, which are rapid food supplies. I think of the mother who is infected with HIV that is not able to get the medicine to then prevent the passing of it to her child in utero. So you potentially see the birth of another generation of of potential AIDS orphans.

I think about what's going on with famine in Gaza. You know, you've got a scenario in which the development community has been hollowed out and here we have this immense crisis, emergency, and everyone's work is now cut out for them even worse than before because of the dismantling of tried and true and highly monitored American entities. I mean, look, I spent so much time, I got to travel to 14 countries to work on religious freedom, to work on COVID vaccine efforts, to work on clean water, to work on hunger, on and on. But I also spent a heck of a lot of time with Capitol Hill and the oversight of Congress, Republicans and Democratic leaders. We were always, always, always being monitored and evaluated by the US Congress - as it should be. And so the notion that there was rampant waste, fraud, and abuse across the entire agency is hard to fathom when we had so much oversight from Republican and Democratic leaders.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Well, and to have such a completely morally bankrupt person like Elon Musk making these calls and his little minions, it's just one of those things where you're watching it happen in real time, you're like, I can't believe this is happening. And is anybody going to stop this? But no one did. I'm glad that there may be a little bit of the remnants of the AIDS effort around the world.

I thought of you at the time. I still think of you and the work. But I think, as you said, more importantly, all of the people who are suffering because of it. And it's just one more thing that drives me actually insane about this administration.

ADAM PHILLIPS:

Well, I think about Republican leaders like David Beasley, who ran the World Food Program. I mean, he's a world hero. When he was running the World Food Program, the whole entire program received the Nobel Peace Prize. And Beasley has tried to reach out to Elon Musk and others to do their part. I'm a prisoner of hope, I can't help but hope that people can right some of these disastrous decisions, but we've got our work cut out for us for sure.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Well, I love that you're a prisoner of hope and this work requires it.

You know, one of the things I'm asking everybody to offer is, what's the one thing you would like people to do? I had Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum, who you probably know because she was involved in the religious freedom movement. But she said, no one can do everything, but everybody can do something. So I am curious, as you think about the work you're involved with, but more broadly in this moment, in this trajectory of our nation as well as the world, what's the one thing you would like our listeners to consider doing?

ADAM PHILLIPS:

I've been thinking a lot about that for myself this summer, and I might have a bit of a curveball for you on this one, but I think each of us might do a radical inventory of our time and how we consume our information with our time. And I know for me, at least, I need to radically reimagine my relationship to media. Not to turn it off, but to look at ways in which I can get the information I need in a synthesized way, maybe.

But then repurpose that time or re-steward that time for neighborhood conversations or simple curiosity moments with folks that I wouldn't normally interact with, maybe because my eyes are glued to my phone on the subway or maybe because I might even be afraid of the flag or the sign that's in my neighbor's window. I think if each of us, myself included, could rethink how we spend our time consuming information and maybe repurpose it to be curious in our neighborhoods, maybe that's one way we can find our way through this mess.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Adam Nicholas Phillips is the first-ever CEO of Interfaith America, which inspires, equips, and connects leaders and institutions to unlock the potential of America's religious diversity. He's also an ordained pastor and the author of Love, Light, Joy, and Justice, How to Be a Christian Now.

Adam, thank you so much for joining us on The State of Belief.

ADAM PHILLIPS:

Wonderful to be here. Thanks.