State of Belief

Book Bans vs. the Right to Read: Kelly Jensen and Rev. Amos Brown

This week on The State of Belief, host Rev. Paul Brandeis Raushenbush welcomes Kelly Jensen. She’s a passionate advocate for intellectual freedom, democracy, and the right to read. As an editor at Book Riot and a former librarian, Kelly has been at the forefront of the fight against book bans and censorship. The urgent conversation covers the growing wave of censorship, the role of religious extremism in book-banning efforts, and what we can do to safeguard free expression and democratic values.

Kelly shares her personal experiences and insights on the emotional impact of censorship, the importance of diverse stories, and how communities can come together to support libraries and schools. The discussion includes practical steps each of us can take, such as attending library board meetings, writing letters of support, and engaging in local elections to protect the freedom to read.

Later, Paul is joined by Rev. Amos Brown, the longtime president of the NAACP of San Francisco and a lifelong civil rights leader. He tells the story of loaning the Smithsonian Institution precious personal items – a historical Bible and the first book about Black American history – and how, seemingly in implementing an anti-diversity executive order, the Smithsonian attempted to return them. (He notes that most recently, there seems to be movement toward reversing this decision.)

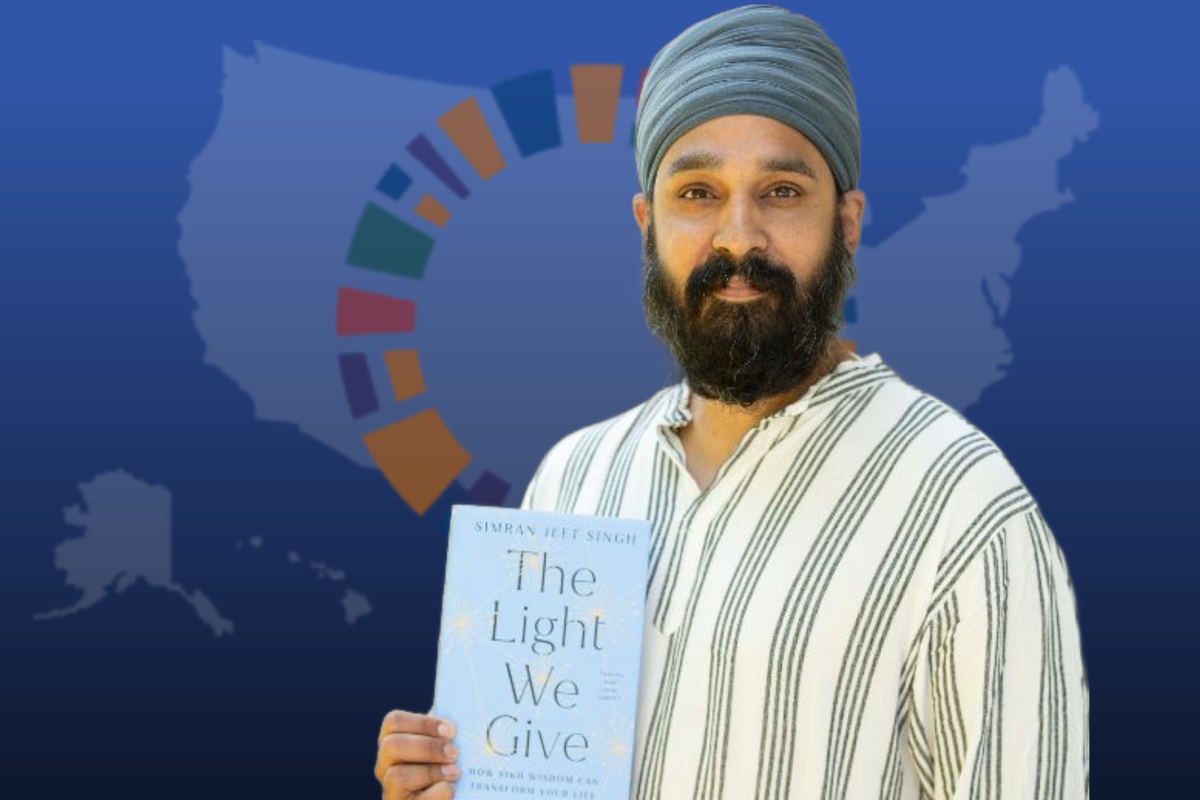

Kelly Jensen is editor at Book Riot, the largest independent editorial book site in North America. Her weekly newsletter tracking violations of the right to read and opportunities for advocacy is titled Literary Activism.

Rev. Dr. Amos Brown is a longtime pastor of Third Baptist Church in San Francisco, a congregation attended by Vice President Kamala Harris. One of the very few students at Morehouse College who were taught by Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., Amos serves as president of the NAACP San Francisco branch.

Please share this episode with one person who would enjoy hearing this conversation, and thank you for listening!

Transcript

REV. PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH, HOST:

Kelly Jensen is a passionate advocate for intellectual freedom, democracy, and the right to read. As an editor, writer, and former librarian, Kelly has been on the front lines of the fight against book bans and censorship, shedding light on how these issues intersect with broader threats to democracy and religious freedom. Through her work at Book Riot and her extensive research on challenges to access and information, she's become a leading voice in the movement to protect diverse stories and ensure that all communities, especially young readers, have access to the books that shape their understanding of the world. Today, we will dive into the growing wave of censorship, the role of religious extremism in book banning efforts, and what we can do to safeguard free expression and democratic values.

And so, Kelly Jensen, welcome to The State of Belief!

KELLY JENSEN, GUEST:

Thank you so much for having me. And I'm really excited to have this conversation with you, even if the topic isn't always the happiest to talk about.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

You know what? It's happy if we make it happy, because we're pushing back against something so bad and so pernicious and dangerous. And the fact that we're talking about it and the fact that our listeners get to hear your voice as inspiration on what we can all do - so I'm glad, even in the face of all that we're up against. And let me start just by the way I like to start with people these days, which is a very basic question, but feels essential: How are you doing? And how are you caring for yourself in the face of all that you are seeing and all that is coming at you? How are you doing personally - your mind, body, spirit?

KELLY JENSEN:

It's been rough, I'll say that. And I add to that, though, since I started really focusing on this as we've seen the rise in book censorship and in attacks on public schools and public libraries, I don't think that my experience or my feelings have changed since the beginning. It's been rough since the start.

I will say that I think in the last four, five, maybe even six months, I felt a little bit more optimism in the sense that I'm really seeing more people understand what's at stake and what's happening. And they are showing up in ways that so many of us who've been doing this work and have been begging for this kind of engagement, it's finally happening. And I think that that is really worth pointing out and saying. And something that somebody said to me, once, when we were talking about book censorship - and this is like 2022, 2023 - was that what gets me up in the morning is not the same thing that keeps me up at night. And I really have stuck with that. You know, the days are long and they're hard, but seeing people understand what's going on and stepping up to make change really helps keep me going.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

I think that's a really important point. In some ways, the most beneficial to our health, our well-being, is really solidarity: that other people see us and other people appreciate us, but also that people are willing to show up with us and that it doesn't feel like we're crazy.

KELLY JENSEN:

And that's a huge part of it, too, because I very much remember, in 2021 when this really started to pick up - I was telling people who worked at public schools and public libraries specifically - I said, you really need to not put anything in email because these people are going to FOIA and they're going to share it. And you are going to bencolored as the type of person that you're not. And even if it's good news, you're celebrating that you got a grant for more queer books in the library, they're going to turn that a different way and you are going to become this target.

I was told I was overreacting, that I was saying too much, and I wasn't. And I feel in some ways like now people are really understanding that that kind of insight isn't meant to hurt them, but rather to protect them from becoming the target of the day, becoming the new person who is colored in a certain way by certain Twitter accounts, or Facebook.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

One of the ways that I became so passionate about this fairly recently was when I went to meet with the Policy Corps at American Library Association. And I was very interested in censorship and how it was manifesting itself as an expression of White Christian Nationalism. But to be in a room where people were literally in tears talking about the ways that librarians have been targeted, whose lives have been - people have been doxxed, people have been called “groomers”, - this incredible attack of a community that is trying to make the world a better place through stories and through information. And it really hit me as, like, oh, these folks are on the front lines, but that nobody is appreciating what they're dealing with on a day-to-day basis.

And just being in a room, my heart was breaking because I was like, I don't think the public knows the way that librarians are being targeted personally in this moment. You're a former librarian and maybe you consider that one is never a former librarian. Maybe once a librarian, always a librarian. But talk a little bit about the emotional impact of what is happening right now.

KELLY JENSEN:

One of the things that I think about and try to mention as much as possible is that most people, - and we know this through research - most people love their libraries. Most people also enjoy their public schools. A significant number - and I want to say it's in the 80s to 90s in percentage - trust their public librarians, trust their school librarians. These are really, really great facts and statistics, and yet it that appreciation that sometimes can make people not realize what's actually happening. Because they appreciate it, and they know so many people do, they aren't thinking about the tools and tactics being used by that small percentage who are causing the problems day after day.

So for a lot of the average library users, they just don't know, and that's not their fault. I think that there has been a better understanding of the importance of showing up for your libraries, particularly in the last year, as more and more of this has gotten to your average Joe who loves the library and has just never needed to advocate for it because it's always been there. And I think we're seeing that show up with people learning a lot more about what their libraries do, learning a lot more about how they're run, and learning a lot more about how the different structures within their community impact that.

You know, a lot of people didn't know the role of library boards and the role that they, individuals, have with library boards. Whether they're elected or appointed, a citizen showing up to a library board meeting and giving feedback, positive feedback, simple positive feedback is huge. And I think that for so long, just because it's been an institution people care about, they've forgotten that they still have to do the good things to show up for their libraries.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

I’ll just mention, two years ago or so, I went down to Southwest Florida, and we were starting a new Interfaith Alliance down there. And one of their priorities, as they formed, they were like, we want to deal with censorship. Because that county, Collier County, it had something like 600 books taken off the shelf. I went down there to give a talk. And the headline was, 600 Books Taken Off Shelves. And I think it was a wake-up call.

And one of the things that I've been working with ALA and others about is like, actually, a lot of the attacks are coming from people who are using religion as a pretext, saying, my religion says that my kids shouldn't be exposed to this. And so they're attacking, obviously, LGBT or anything having to do with that. Black books, you know, books that feature Black characters are taken off the shelves because that's somehow intimidating.

And then, also, what people are less likely to know is that often books that have Muslim characters or Jewish characters or Sikh characters or Hindu characters that are not White Christians are intimidating. And so one of the things that I've been kind of hitting the campaign trail about is, this is a religious issue. This is a religion issue, because if you take away stories, you're taking away religion. There is no religion without stories. And if you're taking away the stories of diverse communities, you're basically establishing one religion as the normative religion, and all the others are allowed to exist - or even maybe not. And so I just think it's really important to understand why it's so important, Kelly, the work that you're doing, and why I feel so passionate about it.

KELLY JENSEN:

This makes me think of two things. The first being that the First Amendment protects five freedoms. What is really important to understand is, an attack on one of those freedoms is an attack on all of those freedoms. So you don't get your freedom of religion by curtailing somebody else's freedom of speech. These things work together, right? And so it's really important to understand you need those diverse books there in order to have religious freedom. Access to a wide range of perspectives opens up your understanding of your own faith beliefs. It gives you a view into the world. And that is the foundation of every religion. I don’t think I’m wrong, here.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

You can't have religious freedom here if you curtail religious freedom over there. You can't have freedom of speech by curtailing other people's freedom of speech.

I'm going to give you a confession. When I was at Huffington Post, I wrote a provocative piece for Banned Books Week, because we had them even like 10 years ago. I mean, it was going on. But it was confronting my temptation to ban books. And it was a conceit. I kind of set it up, the banned books list, like Harry Potter, all this kind of silly, silly stuff that was being banned. But I was like, would I like people not to read really misogynist stuff? Yeah, I would rather people not read it. Would I rather people not read terrorist recruiting stuff? There's lots of things that I don't want people to read.

But the conceit was how important it is that the antidote to bad speech is good speech. And that even if you don't like something, celebrate another thing and lift that up. And that's the important idea. And this is Whitney vs. California, Brandeis said, the antidote to bad ideas is better ideas. And not that we're pitting ideas against each other, but I just, the impulse to say, “I don't want to see that” is so dangerous and pernicious. And you feel so righteous… And so I think that this righteousness, that those who want to take things off the shelf because “We're protecting the children.”

So talk a little bit about what have you viewed as the most effective way to kind of counter that narrative. We're protecting, and you're trying to endanger… How do you talk about this in a way that you feel will persuade the most people about why they need to be in the fight against book banning?

KELLY JENSEN:

To buy myself a little time as I think about this, I want to go back to your last question, because what you just said really teed up a thing that I wanted to make sure I mention in this - because it's a thing that I've been talking about a lot more because I've seen it come up a lot more, and it's this idea that there are people out there who think we should ban the Bible in sort of a retaliatory way to these book bans. You know, a library board will talk about all the inappropriate things that are in this queer book, this book by a Black author - and then it'll be countered with, well, have you read the Bible? There's way worse stuff in there.

And for me, this is one of those things that makes me the most furious for a couple of reasons. One, we don't end book bans by banning books, right? Even if we're trying to be kind of tongue-in-cheek about it, it's really a waste of time and energy on the part of everybody involved. If you do file a formal challenge against the Bible in a public library, that's time and money that this committee now has to spend reviewing that and going through the process, rather than actually doing their jobs and supporting the library. That's part one.

But part two is that we really have to think, that most people who read the Bible, who appreciate the Bible, who study the Bible, who take its lessons very seriously, are also against banning books. The number of people who are banning books is tiny. To then think that this is retaliatory is cruel in a lot of ways, because it is creating enemies out of people who are on the same team as you, who are trying to preserve intellectual freedom.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

I think this is actually really a great answer to what I said. And the other thing about people reading the Bible is that the fact that there is incest in the Bible and brutality in the Bible doesn't mean that people reading it aren't able to discern that this is not saying, okay, I should do that. You could have discerning people read the Bible. And you could have discerning people read a story and say, okay, I understand the message there. And we don't want to dumb down the reading population. We want to say people can handle it. People can handle it. And if it's not for you, don't read it. But I think that's so important, because I hear that all the time: Oh, we should ban the Bible, then. And I really appreciate you saying, this is time that librarians and library boards have to spend that they should be doing other things that libraries are really meant to do. So, okay, banning the Bible is not a good tactic.

Kelly, Book Riot is amazing. Can you tell us a little bit about Book Riot and the work that you do on Book Riot? Because I want to make sure people understand that that's a great resource, as well.

KELLY JENSEN:

Sure. So Book Riot is the largest independent book website in North America. We know that for a fact. We don't know globally, because we don't know what's happening in other places, in other languages. So Book Riot covers pretty much anything when it comes to books and reading, book culture, reading culture. We cover things from your list of best whatever genre books, to funny things. We've got one writer who, when she writes about comics, it's a delight to edit because it's so funny, even if it's not a thing I know very much about. And we also cover a lot of news, and that's really where I, since I started working at Book Riot - I've been there for 10 years full-time, 11 years with part-time work beforehand, and Book Riot's been around, I think, 14 years this year.

I was writing stories about censorship as they came up, because they weren't coming up that much. They were happening, but it was easy to write a piece or two a couple times a year about a story that was blowing up. But as I was still doing this in 2021, I was like, I can't keep doing this. I need to find a way to capture the moment and what's really happening here, because a one-off story is not enough to kind of give this sense of a rise in book bans.

So it was, I think it was August 2021, I approached my boss and I said, hey, what do you think about a weekly roundup of these stories? Rather than going in depth to all the stories that I was finding, finding a way to include as many links to as many stories as possible; to archive this, to create this database of what's been going on, and to use it as a way to acknowledge what's happening - but also to create a record of what's happening. My boss and I joke about this now, because she said to me, do you think that we'll have enough for this thing to kind of continue? And we both wish she were right about that. You know, here we are in April 2025, and these things are taking me hours and hours each week to put together, because there's so much going on. But the reverse of that is, when I read a story about what's going on, I've created this database that I could go back historically and see what's happening.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

So how could people find that? Is it a weekly email as well?

KELLY JENSEN:

Yeah, it is.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

So could people sign up for that?

KELLY JENSEN:

Sure can. It's called Literary Activism, and it's one of the newsletters at Book Riot. You can sign up for the newsletter, have it sent directly to your inbox. Those come out on Friday. And then myself and other editors and writers on the site also send other stories to this newsletter. So you might get extra stuff every week, as well.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

I was very honored, I wrote an op-ed and included it in that. Let me just take a step back and find out a little bit more about you, because you're so on the front lines of this. Did you train as a librarian, or as a writer? What's your background that brought you to this moment?

KELLY JENSEN:

My background is actually in both. So, I thought I wanted to go into journalism when I was in undergrad. But in high school I worked in a library. I was a library page. So I'd been in libraries since I was little, and then worked in them starting when I was pretty young.

I went to a small private college, and had the opportunity to do a lot of writing for the newspaper. I did an internship with my college's library. And these two things were always connected to me, because when you're a librarian, you work to connect people to information - just as when you're a journalist, you are informing the public of the facts and what's going on. So these two things work together.

I graduated when journalism was on the downhill. Digital media was rising, but it wasn't what it is now. And so I realized that going into librarianship would maybe be the option to start. I went to library school and worked in public libraries for several years. And while I was doing that, I was also writing. I wrote for Book Riot for a little while. I'd done my own thing for a while. And when the opportunity arose to go to Book Riot full time, I went that direction, knowing that I could cover issues related to libraries, that I never had to really leave the library world. I could just take it in a different direction.

Like I said, I've been at Book Riot for 11 years now and have just stayed connected in the library world through writing, through the stories people have shared. And one of the questions that I get that ties into what you asked is, what made me so passionate about the issue of book censorship? And the answer is, one, in undergrad, I got to do a really cool senior capstone project with a group. And it was kind of inspired by that internship I did in my undergrad library, where my advisor had asked me to research three books that had been banned, why they'd been banned, where they'd been banned.

And I can't remember off the top of my head the name of the book, but the writer was an Illinois librarian, and he had compiled just these stories of books that had been banned, where, and why. I want to say his name was Brian Doyle. Doyle, the last name, for sure. But going into this book and reading through it just blew my mind that this was happening as much as it had been happening. And that there was this record of it, to have down on paper that this was happening. Because if it's not on paper, it didn't happen. If there's no historical record, it didn't happen. I took that with me into this senior capstone.

This capstone was a project about censored children's literature. My group and I worked on common books that had been censored, why they'd been censored, and why this was such an issue. As you can probably guess, that went with me then when I went to library school. And then when I took my first library job, I had a challenge to a book in the collection. It was an audio book in the teen collection, which I oversaw. And the parent had slipped a letter into the audio book saying that she thought that the book was completely inappropriate for her daughter. She was really disgusted that we had it. And she didn't think it was appropriate.

It wasn't a formal challenge. There was no, like, what kind of outcome she wanted. But I really sat with that for a long time. This audio book was in the teen section. The teen section was for sixth grade and up. And she was upset that her sixth grader had picked up this book, rather than take responsibility for not looking through what her child was borrowing. Instead, the fault became mine.

I didn't do anything with that one. It kind of blew over. But it was a really good first experience with this, because at the next library I went to, I had a challenge to another book. And this was a juvenile graphic novel that had been really well decorated with awards. There's a scene in there where the prepubescent boy has a very common male experience of being an adolescent. And the mother wrote this really long letter about how inappropriate it was for this to be in a graphic novel and that this book should be removed from the library.

Fair enough. Again, no, like, what she expected from it. But my boss was like, I think she's right. And that, to me, was such a moment of, wow, why am I not being supported in having this book that is perfectly appropriate in here from somebody who should be saying, oh, this book belongs here?

I didn't do anything with it. In fact, I put that book in a pile of stuff and let it sit there for a couple of weeks just to see what would happen. Is my boss going to come back to me? Is this person who complained going to come back to me? Because again, there was no formal paperwork filed here. And it blew over. Nobody said anything to me. I put the book back on the shelf. That was the end of the story. But it had always sat with me that something so common for young people, written in a way that was accessible to young people, was deemed as inappropriate; and that that point was not only brought to me from a concerned parent, but that my boss agreed with it.

I don't know if that planted a particular seed in me, but it's a thing that I come back to again and again, just feeling unsupported in my expertise, and my deep desire to make sure kids are represented in their collection.

You know, I'm going to tie this back to that question you had asked about young people. Young people are the most marginalized group in our society. There are not people standing up for young people. And because they're young people, they don't quite have the capacity to stand up for themselves the same way that we do as adults. And so I think about this all the time, and think about how, for so many young people, these books are lifelines. This is where they're learning things. This is where they're seeing themselves. This is where they're seeing the world. And to take that away from them is to further push them to the margins and to further tell them: what you need doesn't matter. I get to decide what you need.

And that message stays with them. It stays with them through childhood and adolescence. It stays with them through adulthood. And we need kids who are seen for who they are, and who are given the tools to become fully who they are.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Right. For me, I picked up - and I'm fortunate, I have no idea how it got there - but in my family's library was Baldwin's Another Country. And I was in my teens, and it was the first time I saw a gay love story. I'd never been able to sit with it on my own and kind of go through it. And also, in addition to that, compounding its goodness, was to really sit with incredible writing about the Black experience, which I hadn't really done. So not only did I feel my own life reflected, I got to get a literary insight into another life that was completely different than mine.

And I still remember the experience of reading Another Country and being like, am I reading what I'm reading? Because this was early 80s and there weren't a lot of good stories out there at that time that I had access to. And today, we're in a moment where I’m very fortunate that my kids go to a public school in New York City where it's not really pushed on anybody, but there are stories that have same-gender parents. And that is just not a thing. It's not indoctrination. It's just like, okay, this is part of the story of this neighborhood and this community. And so I do think for young people to see that and for it to be part of the world, it is so important.

What difference, if anything, has it made to have the election of Donald Trump and a lot of permission granted, maybe is a way to say it, of really bad behavior around the country? How have you seen this moment accelerate, or perhaps become, even more so, a moment of crisis for the freedom to read in this country?

KELLY JENSEN:

So I have had the fortune to talk at a lot of libraries and in a lot of conferences for librarians about what's happening with book bans and censorship nationwide. Because as much as a person at a library is informed of what's going on, they don't know what's happening everywhere. They can't - they shouldn't, right? But having that knowledge is also important.

So I felt really fortunate to be in the position to kind of summarize and put action steps into place for librarians and libraries to think about what's going on, and how they can protect their own institutions. A couple weeks ago, I was doing a talk at a suburban library here - I'm outside Chicago - and it's a talk I did for a different library a year ago, before… Not even a year ago, it was in October, so before the election. The audiences were both very receptive to this conversation, were eager to have it, but the conversations were very, very different.

That October one, there wasn't a whole lot of engagement with the audience, because they were there to learn something new or pick up more information that they hadn't already learned. The second group - and again, demographics in these communities are very, very similar. So there's not a big difference in terms of who showed up. But at the second one, they wanted to have a conversation rather than to be talked at or talked to, because they were very aware of what was happening. They had seen it. They had started to see these big headlines about what was going on. Just the level of understanding how national-level politics were impacting them on the local level has shifted - and shifted very fast.

I think that this is good in the sense that it's getting people engaged, but obviously bad in the sense in that people shouldn't have to be worrying about this, that this shouldn't be happening. I had mentioned at that talk how important local elections were, and these people were so eager to talk about that, how they were researching their candidates, that there had been a recent school board election for a neighboring school district that the kids had spoken up about one of the candidates being a bad candidate, and how the kids were convincing their parents of the importance of these elections.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Wow, that is great.

KELLY JENSEN:

Yeah, outstanding, right? And so just the level of awareness of what's happening, really happening, I think, has changed. And this particular group, I said, you know, show up to your board meetings. If you can't go, write a letter, drop a comment card. This stuff is really important, because the board wants to know that the library is doing a great job. And numerous people at this meeting were like, where can we get the cards? We're going to fill them out now. And I'm like, this is the energy; I wish it had been there before, but it's there. And so I think it's now harnessing it to continue through what will be a long period of time. I would say four years. We don't know that. We don't know how long this might happen.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

People are changing. I do want to kind of underline that there are things you can do right now. You can show up for library boards, for school boards, and really let your voice be heard. And one of the things that I talked about in the op-ed and really, really strongly believe is that diverse religious communities that support the freedom to read, you're the best antidote. to these folks who show up and say, I represent religion and my religion says, and I'm speaking for the religious voice and I'm speaking for the moral voice.

We can't cede that space, because they're using it as a sledgehammer. And they're saying, okay well, you know, whatever else you say, this is my religion, it trumps everything else. And it's like, no, because the majority of religious folks don't support this. So it's just really important that if you are a religious person and you are going to these meetings, in any case, you can also say, I'm an observant Jew. I am a committed Christian. I'm a practicing Hindu. Whatever is your tradition, you can name it, and then speak out of that. It can't hurt to have that brought in, because we just need to make sure we never cede the religion space right now around book bans, because we're giving them more than they deserve.

So specifically: the three things that you've mentioned are showing up to meetings, writing notes, and there's library board... Each library has a library board. I don't think I knew that until last year. I kind of consider myself as an aware person. I didn't know there were library boards. So, library boards, school boards. What else?

KELLY JENSEN:

Library boards, school boards, city councils. Those are really great places that are going to impact everything you do in your day-to-day life. These are the people who are making decisions about what happens in your community. So knowing that they're there, knowing that you are, as part of the public, represented by these people, and therefore have a right to show up to these meetings and share your opinion and your insight - do that. It's so important. Library boards are a mix of either appointed positions or elected positions. So if you are passionate about libraries and passionate about helping strengthen your library, you could always run for a member of the library board.

One thing that I also like to talk about - it may be a less deeply committed, but still important role in the library - is consider joining your library friends, or their foundation. This is the fundraising side of your library. So these are people who are typically running, if your library does an annual book sale or has books for sale in the library, that's one of their big fundraising things. And the friends are there to support the library financially. I think in the next few years, especially as we're seeing federal funding that has paid for a lot of really important stuff state to state, as that disappears, these friends groups or foundations, sometimes they're called, depending on the library, they're going to take on an even bigger role.

And I think in terms of folks who have a religious community, this is such a great opportunity for you. Get involved with your friends, and then you talk to your friends at your church and say, hey, the book sale's going on this week, let's all go and purchase some books. Library’s having a fundraiser at X, Y, Z place, wouldn't that be a great outing? And you're then inviting a community and showing that your community is not represented by those loud voices, by those voices who are trying to strip away these incredible institutions that anybody is welcome to, that anybody has access to.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

And you raise a really important point about funding, because censorship doesn't only happen through these direct, individual, one-by-one; if you're targeting libraries - and you have a headline right now, “Ohio's Republican Budget Proposal Destroys Library Funding” - this is a way of starving libraries from being able to serve the public. So there's another important aspect of the book banning fight, which is, make sure your state legislative body is not starving libraries.

And this is all punitive. This is all direct attacks. I mean, it's kind of cool that libraries have become this kind of radical space of welcome, which they always were, but they're viewed with suspicion by the authoritarians, which is true. Sources of information, places where people gather - that's all bad for authoritarian regimes. And so libraries are those. But that's another place that I think those of us who want to be active in the fight against book bans might want to also look at what's being voted on in the budget hearings.

KELLY JENSEN:

And just be aware, too, of what your library budget is, where the money is, where it's coming from. None of this stuff is hidden. It's probably right on your library's website under their board information. They'll have this material in there. You can view it. You can learn from it. And I think, too, a lot about how important it is to show up, not just to the library board meetings and the school board meetings, but then those city council meetings too. And just say, I love these institutions we have here. They're great.

So my community does a really big Pride event. We are a pretty small town in terms of being in the Chicago suburbs, but we have a very active Pride community here and have always done big Pride events. I want to say for the last seven or eight years, it's been a big thing here. Until the last couple of years, there was no pushback. But as we've seen rhetoric around this, there's been more pushback.

So after the festivities wrapped up this last year, I sent an email to city council and I just said, hey, It is so cool we do this here. It is so cool. We are so welcoming. It is so cool to see all of these churches who show up and have people in the parade who have tables at the Big Pride event. This is an open and welcoming event for people of all backgrounds. And it is incredible we have this here. Basically, that was the email, just a few paragraphs of how awesome it was. And not one, but two, maybe three people responded from city council and said, we never get nice emails like this. And it was one of those moments where I was like, you're right. You probably just get the complaints.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Exactly! That is so important. I remember after the Respect for Marriage Act passed in the Senate, and we were really involved in rallying religious communities, and we presented a letter, national religious groups supporting the Respect for Marriage Act. It passed, and we were going through the Senate, and we stopped by a random Senate office that had supported the bill. And we just went in there and we said, hey, we just want to quickly thank you for voting for the Respect for Marriage Act. You know, we're a religion and democracy organization, bada, bada, bada. And I'm a reverend, and I gave them my card.

They said, we never get this. We got so much negative around this. We never got any positive. That is huge what you're saying. And it has to do with book bans, but it also has to do with everything. If someone shows up for you, thank them. You know what I mean? Because they are getting lots of pushback; and instead, just remember that they need to feel like people have their back. Otherwise, they're going to lose their spine.

KELLY JENSEN:

I tell people that it's really important to stay informed of what's going on everywhere, but we're in such a deluge of information and of changing things and negative news that to even get through the day can be difficult. This is just a barrage, right? So, I tell people to pick one thing. Focus on one thing that you are passionate about and let that be where you spend your time and energy.

So, for example, you're going to write letters once a month to your city council, your library board, and your school board that just say, hey, thanks for what you're doing. Hey, I saw this really cool play by the students at the school. They did an awesome job. At the library, you had this great display of books and it introduced me to my new favorite author. Thank you so much for doing this kind of stuff. You put that on a calendar once a month, you dedicate an hour, you have done a lot of really incredible work.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

You know what, running an organization - and you know this too - whoever gets that letter is going to show it to people: Look what I got. So it's not just a person. It's also like they're going to show it to someone who's attacking them and say, well, you say that, but I'm going to read you a letter I got. And that is fuel. And I just love that you offered that example.

You know, as we wrap up, I actually ask everyone, like, what's the one thing you hope people will do? And it sounds like that's one of the things, is like, take time. You can say another thing if you want to offer another thing. But it is important not to think like, oh, if I'm not doing everything, I better just do nothing. What's the one thing that you really hope that, especially around this moment, around freedom to read, the threat of book bans, what would you like for our listeners to take away as that one thing that they can do?

KELLY JENSEN:

You know, those letters are important. Show up to a board meeting. One of the things that made bookbinding groups so successful early on is that they showed up to these board meetings like it was a party they were going to. So you tap three or four of your friends and say, hey, we're going to go to the next library board meeting. It's at 7 o'clock. We'll stay till it's over. And then afterward, we'll go out and we'll talk, what we heard, what we learned. This can be an opportunity that during public comment, you just go up and say, I'm so glad that the library exists. Or, you know, if you're into visuals, you can show how worn your library card is, because you use it so much, because you're there so much, and that kind of stuff. It's not only important because it reflects on what's going on at the library; it's important because it gets on the public record. Your name and what you've said is now in the documents that live with this institution. So as you said, you're going to share the letter that you get with everybody. But you're not only just sharing the letter with everybody; it's also on public record. So that lives with that institution. And that is proof that it's not just the loudest, angriest voices who are being heard. So too are the people who are really happy with the services. You know, that's my big thing.

And my second big thing is to vote and pay particular attention to your local elections. Yesterday my state had consolidated elections that determine school board and library board members across the state. Know who's running, know who cares about these institutions, and who wants to make them better - because not everybody who's running has that as their goal. And so voting for people who are going to really support these institutions that are becoming more fragile is really crucial. And that's an easy thing you can do.

There's a really great podcast episode of Jon Favreau's Offline. And I wish I could remember which one it is off the top of my head. But he had a guest on who was talking about local politics. And he emphasized that when you vote in these local elections, tell people. Tell people who you voted for. Send an email and say, hey, did you get out and vote today? If not, you should. Here's who I voted for in the school board and the library board and why. I think they're great candidates. Your personal touch to people in your network makes a huge difference.

You know, you can hear from all of the various parties and organizations saying, get out and vote. It's important to vote. But if your neighbor sends you an email and says, hey, I really think you should vote for John Smith for school board because he cares about the kids there, and he has advocated for them to have better funding so that teachers have better salaries, that they have up-to-date textbooks. That's going to get you to the polls faster than any party saying, get out and vote. And so just remembering that you have tremendous influence in your own networks as well. And to use that, that matters.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Kelly Jensen is a leading advocate for the right to read and an activist against censorship and book bans. A former librarian, she is a longtime editor at Book Riot, and she has a great weekly email that you can sign up for called Literary Activism.

Kelly, I want to thank you so much for your work and all that you do. I really appreciate you joining me here on The State of Belief!

KELLY JENSEN:

Thank you for having me, and thank you to everybody for tuning in. I’m really excited to see more folks who are showing up for their libraries and their schools.

...

REV. PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH, HOST:

Well, Reverend, I was glad to get a chance to speak to you last week. I wanted to follow up with a conversation from your lips about how the Smithsonian apparently does not want to tell the story of your experience in the Civil Rights Movement, and appears to be rolling back efforts to tell stories about civil rights in general. And I just wonder if you could tell us how it happened that they sent back your Bible and all sorts of important pieces of history that apparently are no longer able to find a home in our history museums.

REV. DR. AMOS BROWN, GUEST:

Well, needless to say it is very much disconcerting, and I'm dismayed that we have this, I would consider first of all, a lack of continuous communication and respect for the significance of percentages and happenings that Black Americans have been in leadership of in all areas of life. And it boils down to what one said in a great quote, “People tend to hate each other because they are fearful of each other. They're fearful of each other because they do not know each other. And they don't know each other because of a lack of communication.” A basic human trait, communicate, collaborate, and cooperate with each other.

Now since 2016, on the heels of the Smithsonian contacting me about considering the loaning or donating to the Smithsonian some of my artifacts. And that was requested because they knew, from the very beginning of that institution, of my long involvement in the civil rights and human rights struggles around the world. And I initially loaned them a Bible that was my father's Bible, was now over a hundred years old. And I was always motivated by Micah 6:8: “What does the Lord require of thee, O man (or woman), but to do justice, love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God?” That passage really inspired me. And all of my engagements in the struggle have been motivated by that passage.

And then I got from my father's bookshelf, at the age of thirteen, a copy of the oldest written history of the Negro race, that was written by a Baptist preacher named Rev. George Washington Williams, who wrote that book in 1880. It was then titled History of the Negro race from 1619 to 1880. And he was pastor to the great Union Baptist Church of Cincinnati, Ohio when he wrote that great book.

So we had here two of my artifacts representing history and a spiritual book. And everybody should know the significance of those two books.

But unfortunately, a recent happening came about because in these times, there has not been shown a great sensitivity and interest in promoting diversity, inclusion, and equity in this country. We need to come to our senses in this nation and really, with pit bull determination, pursue the notion and principle that we should be one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. And to exclude any group's history, identity, contributions, is unjust. It's bad behavior. It's disrespectful to marginalize certain people because of their race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, or even political affiliation. We should be one family. A beloved community. That's what Dr. Martin Luther King envisioned for this country and gave his life for.

So I feel that we need to just chill, do more communicating with each other, and stop being about this action, for whatever reason, of degrading, of banning, of ignoring anyone's history if it is worthwhile, factual information. We should applaud it. We should make sure that we learn from each other in this nation, and never be rugged individualist, isolationist, nationalist people. We should be global in our outlook and fight peacefully for one world in which we will indeed be a quintessential statement of a beloved world community.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Well, Reverend, I want to say personally, thank you. Just to start with, thank you for the ministry that you have had over these many decades, and the countless people who you have influenced. And they can try to take down your stories and they can try to send back your stories, but that doesn't make those stories any less powerful. And we need those stories today, and we appreciate your words, your wisdom, your inspiration, your vision. And I think one of the deep tragedies of this effort of censorship that we are experiencing all across the country, is people are trying to take away stories of all kinds of people instead of bringing even more stories into the mix.

And that's what I love about what you said about the beloved community, Dr. King's vision. Which is really about how all these stories can come together and be part of one amazing story. And you exemplify that so much in the breadth of your ministry, which of course includes Vice President Harris and many, many, many others in your long ministry, as well as your civil rights activism.

Do you have anything specific to say about what you're seeing as censorship in schools and censorship in libraries across the country?

AMOS BROWN:

It is uncivilized. We are social beings and we should not exclude anyone from the human family. And so true Christians are doing justice, loving mercy, and walking humbly with their God. We need to be communitarians coming together. And even our faith traditions, our religions, should be about bringing things together. The word “religion” comes from that root word which means “ligaments.” What do ligaments do in the human body? Hold things together. And we must become, be always, brothers and sisters. For if we don't learn how to live together, we are going to perish, as Dr. King said, as fools. It's a foolish thing for anyone to think that he or she is the only pebble on the beach, so to speak.

We are a world community. We have various continents that have made contributions to human civilization. And we should recognize, celebrate, applaud, all the good, great things. And also to be humble enough to admit the wrong things that we have done, such as persecuting people and causing anarchy, division, carnages. We should stop that. And just be kind and watch our behavior.

Whenever I left home down in Jackson, Mississippi, my mother would always say, “Amos, behave. Behave. Don't take anything from anyone. If you go to anyone's home, don't ask for anything. Let them offer it to you. Behave.” But since humankind left that rift valley, over there in Kenya and Ethiopia - that's where we came from, according to the paleontologist Leakey. But once we left home and we stepped on beaches, rivers, somewhere, we developed this dichotomous thinking of them against us, us against them, instead of achieving a mastery of that one little pronoun, “we.” We the people. And when we put “we” in our language, and not “They. Him. Her.” But “we.” We are children of that force, that creator, that God, or whatever we like to call it, and we just stop our bad conduct. Bad behavior.

We talk a lot about having conversations, but I think we've had a good number of conversations about these human problems. Now we need to do more to change our conduct. And just as mama said, behave. And we need to hear that. We need to say that. We need to do that in America. But right now, we have too much meanness, too much badness, too many instances in which we have missed the boat of living out our preaching about being a democratic republic.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Reverend, I really appreciate you taking time to speak with us today. It means a lot. And we look forward to celebrating all of your contributions that continue, clearly, to this day. Appreciate you very much.

AMOS BROWN:

I have gotten some conversations from representatives of the Smithsonian about trying to iron this situation out. They have aknowledged that they didn’t handle this thing the best way we should have seen them do it. But I'm always open for reconciliation and putting things back together again.

But right now, with the atmosphere that's national and with the hiccups that have been made by a different staff at the Smithsonian, we have a task before us to not junk each other. If I had a shirt that got a wrinkle in it, I don't throw that beautiful shirt away. I get a steamer. I get an iron. I ironed it out. I steamed it out. And we need to get this wrinkle. This wrinkle. A book banning, this wrinkle of being partial and prejudicial in dealing with people. We should all be able to say, “We the people are working together to create a better universe, a better order, where we will live as brothers and sisters.”

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Thank you very much.

AMOS BROWN:

Thank you for the opportunity of sharing with you. God bless you.

Jewish-Muslim Solidarity: Moral Witness in Pressing Times

Highlights from a Capitol Hill briefing on Jewish-Muslim solidarity as a defense against authoritarianism, featuring prominent Muslim and Jewish leaders and lawmakers. With discussion and inspiration from host Rev. Paul Brandeis Raushenbush and interfaith organizer Maggie Siddiqi.

We The People v Trump with Democracy Forward's Skye Perryman

Host Paul Brandeis Raushenbush talks with Democracy Forward President and CEO Skye Perryman about the first year of the second Trump administration. Skye describes how, amid a flood of policies and orders emanating from the White House, Democracy Forward's attorneys have brought many hundreds of challenges in court - and have prevailed in a great majority of them.