State of Belief

Faith, Power, and Victimhood: the evolution of Christian Nationalism

As Christian nationalism and the far right’s influence on American politics grow, historian Randall Balmer offers a critical examination of evangelicalism and the surprising shifts within its ranks. In his book Bad Faith: Race and the Rise of the Religious Right, he reveals how far-right religious lobbying in the 1970s, fueled by efforts to defend racial segregation, evolved into the dangerous political force threatening democracy and religious freedoms today.

For this week's episode of The State of Belief, Interfaith Alliance’s weekly radio show and podcast, Randall joins host Rev. Paul Brandeis Raushenbush to explore the evolution of evangelicalism, particularly how early evangelicals championed social reform, contrasting with the modern political alignment of those influenced by the far right.

“I think religion certainly contributes to democracy. And some people have misinterpreted what I said, including my dogged defense of the First Amendment, which I believe is America's best idea. But people have misinterpreted me to say that voices of faith should not be part of our political discourse. And I couldn't disagree more strongly. I think people have every right to bring their religious or faith commitments into the arena of public discourse, and I think public discourse will be impoverished without those voices… I have every right to express my religiously informed convictions in the arena of public discourse. But I also have an obligation to listen to others, as well.”

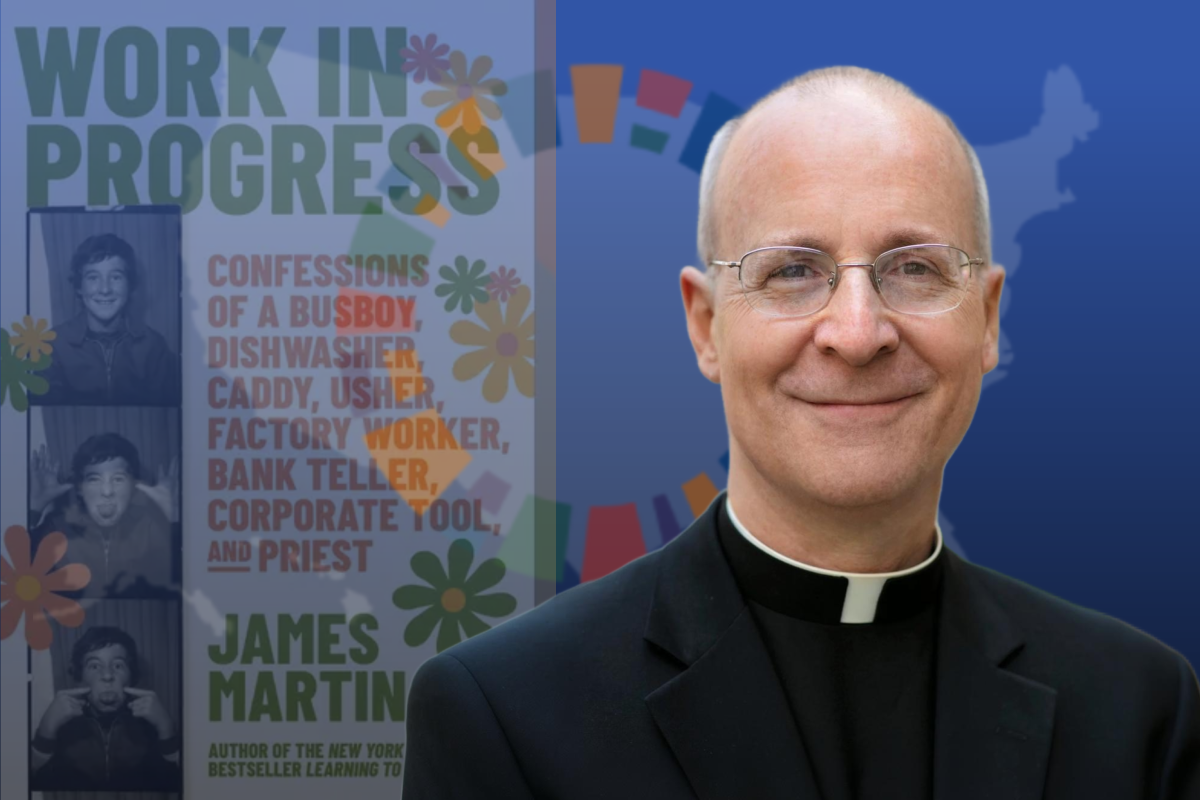

Dr. Randall Balmer, prize-winning historian and Emmy Award nominee. He holds the John Phillips Chair in Religion at Dartmouth College, the institution's oldest endowed professorship. Randall's latest book is Saving Faith: How American Christianity Can Reclaim Its Prophetic Voice.

Please share this episode with one person who would enjoy hearing this conversation, and thank you for listening!

Transcript

REV. PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH, HOST:

A prize-winning historian and Emmy Award nominee, Randall Balmer holds the John Phillips Chair in Religion at Dartmouth, the oldest endowed professorship at Dartmouth College. He's also an Episcopal priest, and as early as 1989, he was publishing books like Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory A journey into Evangelical Subculture in America, Thy Kingdom Come, How the Religious Right Distorts Faith and threatens America,bad faith race and the rise of the Religious right, and most recently, saving Faith how American Christianity can Reclaim its Prophetic Voice. Randall, congratulations on receiving the 2024 American Academy of Religion Martin E Marty Award for the Public understanding of religion. It's so great to have you back on the state of belief.

DR. RANDALL BALMER, GUEST:

Thank you, Paul. It's good to be here. Nice to talk with you.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Yeah, absolutely. Well, you know, this list of, titles shows that you are not new to this game of, like, actually looking at religion in America and kind of raising the flag and saying, hey, pay attention to what's going on in American religion is actually really important and can impact our public life together.

So maybe can you just take us back to a little bit about your history and how you came to really recognize what was happening in America, and especially on the religious right at way back? But what what in you made you your eyes open to that?

RANDALL BALMER:

Wow, what a question. I guess the deep answer to that question is that I grew up as an evangelical. My father was a minister for 40 years in the Evangelical Free Church, and I hasten to add that I honor both his memory and his ministry. So growing up in that world, and what I came later as a scholar to call the evangelical subculture, was utterly formative to me. And evangelicalism is part of my DNA. I, I try to run away from it sometimes. And believe me, in the last few years I really tried to run away from it. But it's it's part of who I am. And I think as I became a scholar, first of all, I went to graduate school really to be a historian of colonial America.

And I kind of stumbled into doing scholarship on evangelicalism rather haphazardly, during my, my, my time at Columbia University. but as I came to that study, that is the looking at the history of evangelicalism And seeing the emergence of the religious right, I began to see this, this great, disconnect between the history of the movement that had shaped me so profoundly and the current iteration of its political sensibilities with religious right. So I'm happy to expand on that.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

But that's I think that's what I love about that. And I just find myself talking to a lot of people who not exactly like you, but with similar profiles, who really come out of that movement and who owe a lot of their, you know, some of the underlying religious sensibilities to that movement. And, and, and who often see, you know, beauty in that movement and are grateful for certain parts of it. And I love that because I think, I think the important, recognition is that this is not a condemnation. When we raise up questions about a tradition's use of religion in the public square and how it's manifesting.

It's not necessarily, although sometimes it can include a condemnation of a tradition that has been so rich and that has been so meaningful for individuals personally, and also how they, you know, evolved as, as, as, you know, citizens of this country. So I love that background. I'm wondering if you start to look back at even of your father's ministry, and this is not a chance for you to, denigrate at all your father. But when you look back with these eyes that you gained once you started being a scholar of religion, did you do you see signs like even in the 70s, or you know, where it's not entirely surprising that this evolution happened already. We were seeing inklings of this. Do you with your with your scholarship, I can you go back even that far in your own experience and recognize moments that might have indicated something like this?

RANDALL BALMER:

That's that's a good way to to to frame the question. I guess I did see maybe in retrospect where it was heading and I but at the time I saw things very, very differently.

I remember, for example, when I went off to college, I went to a little school called Trinity College in Deerfield, Illinois, which was my denominational school, which sadly closed last year. It's really a great tragedy, in my judgment, because it was such a formative place for me. But I remember as a as a first year student there in the fall of 1972, it gives you some idea how old I am. Kind of pleading with my classmates, you know, we Christians, I didn't know any other really real term for to describe us. You know, I realize now we're talking about evangelical Christians, but we Christians need to be involved in politics. We need to, to, be active in the political arena and it it fell on deaf ears. There was just no interest whatsoever in that. And so great the the great irony in my life and my career, I suppose, beginning in the 1970s, is that I was advocating for for political engagement because I was fairly confident that I'll I'll be it, naively so, as I understand now, I was fairly confident that if evangelicals became involved or re-engaged in social issues, they would do so in a way that their their ancestors, their political, or their religious forebears had in the 19th century, that is to say, to, work for the benefit of those Jesus called the least of these.

And particularly as I began to study a bit more about my own tradition. I saw that evangelicals were very involved in issues like prison reform. They were staunch advocates of public education, known as common schools in the 19th century because and they were explicit about this, this was a way to advance the fortunes of those who were on the lower rungs of society. They were very involved in peace movements. I've even run across an instance of a gun control movement sponsored by evangelicals in the antebellum period, and they were very much in favor of women's equality, including equal rights and voting rights, which in the 19th century was a radical idea. So as I was advocating for these things, I was, you know, reasonably confident that should evangelicals begin to become involved in politics in the 1970s, they would surely gravitate to the same issues that had energized and animated evangelicals of an earlier era. Of course, I turned out to be dreadfully wrong.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

It's so interesting because those are, you know, I mean, I yeah, it's it is there's a history and also like where evangelicals meet, you know, that what we began to understood as like the mainline church or kind of the, you know, modernist church, you know, that, you know, my forebears were a part of.

But, you know, Walter Walter Rauschenberg's father, was a hardcore evangelical hardcore, but he was also the one who, when he started a church in Missouri, said, there will be no slave owners that will ever enter this church. You know, I mean, like, he was like his condemnation of slavery and he condemned the North and the South, both. I mean, he was like, not a great guy in many ways, but in some because he was really, really focused on sin. But he really when he focused on sin and he saw slavery as a sin, which he did primarily, he, he, you know, called it out. And so there is like this really interesting tradition within evangelical taking on issues. And then I actually think it's very funny that you went into the 70s, because that's really when, you know, we had the rise of what, you know, was conveniently called the Moral Majority. And then, you know, into the religious right and then the Christian Coalition.

I just, I, I want to like, you know, I want to jump, to our current era and, and ask you, like, the million dollar question. It's, I guess, within, you know, it's possible it's $1 billion question today. Did you see this coming? Like, did you see this? Like what was happening 70s 80s 90s because it was always there. I mean, this like rise of the religion, what we used to call the religious right or the Christian right or the Christian Coalition to to this sort of moment where Christian nationalism or white Christian nationalism is at such a height and such a force. And I mean, I so tell me about like how you understand our current moment, given that you've been writing about this literally for 30 years.

RANDALL BALMER:

You know, I again, I have to say I was kind of blindsided by it. Paul, I, particularly 2016 when the figure came out that 81% of white evangelicals voted for a what, thrice married Former casino operator and self confessed sexual predator. For president, this is the movement that was trumpeting its so-called family values. I was blindsided by that. I have to say, I just I was gobsmacked. I can't I don't know how many other synonyms I can come up with. but again, as I sat down to write bad Faith, which is about, as you know, about the origins of the religious right. It allowed me to kind of, again, look through the historical, tea leaves and say, wait a minute. This probably isn't all that surprising. As you know, with in bad Faith, what I demonstrate, I think without any doubt, I'm happy to to stand on this with with anybody who wants to challenge me. Is that the religious right did not galvanize as a political movement in the 1970s and opposition to abortion.

I mean, this is just it's just utter fiction. And I call it the abortion myth. What drew it together as a political movement was a defense of racial segregation at places like Bob Johns University, but also segregation academies like Jerry Falwell's Liberty Christian Academy that he formed in 1967 explicitly to keep students of color out of the out of his school and also to keep white students out of the the desegregated public school system. I mean, it was just, you know, it's very clear about that.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

You know, I think it's it's worth mentioning like this is, you know, and and I hope you this is meant as a compliment. It's not meant to diminish your scholarship contribution, but it is one of those things that when I read that book and I read your really flawless academic scholarship on it, it did help me change the narrative completely, because I think the very convenient one was like, oh, they rallied around abortion. And and that was really what everybody said, even the people on the left and the right.

But it wasn't true. And, and and it was really your scholarship for me. I mean, other I think there may have been other people who are aware of it at the time at a personal level, but to elevate it to the level of kind of really undisputed fact at this point that the religious right was really founded. It's it's the movement that we know of today as, on the idea of almost as a reaction to Brown v Board of Education and the idea of, of, school integration and…

RANDALL BALMER:

No, and there's no question about that. I mean, it's, it's, it's, you know, again, the book, as you know, is, is flooded with footnotes and anybody who wants to go back and, oh, it's…

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Really amazing, but it's, it's just that and so honestly that that's where if we fast forward to 2016 and we we really, you know, like underline white evangelicals rather than evangelicals. And, you know, I mean, there's I'm sure you saw God in country the Rob Ryan and when Jamaar Thisbe who was, you know, a very interesting, person who we've had on this show, talked about the moment when he saw that all these evangelicals who he thought were his, you know, siblings in Christ and, you know, you know, and he had been hanging out mostly in white evangelical spaces, but he, he when he saw that almost all of them voted for Trump and, and that there was kind of a racial underlining of that.

I just think it's, you know, it's it was it's a devastating moment in the film. It was clearly it was a devastating transitional moment in his own life. But this goes back to that, these the late 60s, early The 70s. and I think that that frankly, I think that the film relies heavily got in country, relies heavily on your scholarship, to really underscore that. So, I mean, this is this is really important for us to remember today because I think, you know, abortion, you know, we I completely disagree with the Christian right's interpretation of that, but I there's a way for me to understand it. There's no way for me to understand this, this lack of ability to to understand that we should be a democracy, that that benefits all people regardless of race. And so or with regards to race. And so I just think that that's a, you know, something that that we I'd be interested in you talking about how you see that manifesting itself now in the kind of white Christian nationalism that we're seeing.

RANDALL BALMER:

Yeah. Well, you know, again, let me just circle back for a moment if I can just say that, please. you know, as I was trying to understand for myself this, you know, 81% of white evangelicals voting for Trump in 2016. You know, then I went back while I was writing about faith and said, well, wait a minute. Let's look at the origins of this movement. And maybe it's no surprise whatsoever. And, you know, the image I think I use in the book is that you can have this beautiful structure, but if it is, if the foundation is rotten, it's it's going to be compromised. And that I think, is, describes the religious right. And the other thing. The other point I want to make as well is that the transitional figure there between Jerry Falwell and and the religious right in the late 1970s and Donald Trump in 2016. The transitional figure is Ronald Reagan. And I know a lot of people don't like to hear that because they regard him as a kind of political messiah.

But let's consider the evidence. Ronald Reagan got his start in politics in opposition to the Rumford Fair Housing Act in California that sought to guarantee equal access to both rental housing as well as purchase of housing. He was an outspoken opponent of both the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Throughout his political campaigns, he kept invoking the specter of welfare queens, women of color, who were living these lives of luxury off the public dole. He also was using the dog whistle of law and order. Of course, Nixon had used it as well, but nevertheless, Reagan was using that. And I think for me, the clincher in terms of Reagan is and people don't remember this, but on August 3rd, 1980, he opened his general election campaign for the presidency in, of all places, and I still can't quite believe it. But he did in all places at the Neshoba County Fair in Philadelphia, Mississippi. The place where 16 summers earlier, members of the Ku Klux Klan, in collusion with the local sheriff's department, abducted, tortured and killed three civil rights workers during freedom Summer of 1964.

And lest anyone miss his meaning. And Reagan was a master of similar symbolism, he declared to that all white audience I believe in states rights, invoking that age old segregationist battlecry. So again. Yeah. Connecting.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Yeah, connecting. That's really interesting. It makes me think we had a, we had Diane Winston on this show a long a while ago, and she wrote a book called Writing the American Dream about the evangelical tie in with Ronald Reagan, which is something I hadn't really focused on, but it was just really, really interesting to hear about that. And this. This ties into what you're saying, and I think it's like, I think one of the things that's, important just to talk about, like the exercise in power and how important power is and the sense of like, you know, I think there's a there's a refrain of, you know, we're, you know, of, of, of white evangelicals or white Christian nationalists, like, we are powerless in the face of these incredible forces that are trying to take away our religion, take away our freedoms, when in fact, they're really they actually have wielded power in a very calculated way.

And I think Donald Trump is a perfect example of that.

RANDALL BALMER:

Yeah. And and I I'll go on to say that I think power is is corrosive. And that's hardly a new observation. I understand that, but particularly for religion, I've I've long argued that religion always functions best from the margins and not in the councils of power, because once you begin to. Crave political power or influence, you lose your prophetic voice. Now, there are all sorts of examples of that, not only with the religious right, but also I'll I'll point out Paul, and I'm speaking myself as well in mainline Protestantism, or I sometimes called brand name, brand name Protestantism. That is to say that in the post-war era, in particular, mainline Protestants and the National Council of Churches were riding high. Yeah. And what happened was that as they became very acculturated to wielding influence within the culture, I think they began to lost their lose their prophetic voice. And they began that long slide that we're both aware of, where mainline Protestantism or brand name Protestantism is is very much on the decline.

So the, the importance I think, of, of faith and religion is to speak from the margins. And that, I think, has been the great downfall of the religious right, is that beginning with Ronald Reagan, they offered no prophetic voice. I mean, you know, Reagan went on a binge of, you know, tax cuts for the wealthy. We all know about this. We don't need to rehearse the the particulars. But where were the dissenting voices at that time? Well, yeah. You have people like Jim Wallace and and others who are doing so, but they don't have nearly the, the megawatts that somebody like Pat Robertson or Jerry Falwell had in that era. And they were utterly silent. They were they were sucking up to power in, in, in craven ways that I think ultimately diminish the power of the faith.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

It's very interesting watching the religion in this current election and how it's being talked about or not being talked about, but also the manifestations of religion. I mean, at the top of the Republican ticket, we do have Donald Trump, who was you know, it's, you know, the way he, you know, I have to get your take on this, this crazy thing he said to the that group of evangelicals, like really, really right wing evangelicals like my, my, my, I'm not going to do the invitation, but my beautiful Christians, my beautiful Christians, just vote this once one more time. I'm going to fix it. This is you'll never have to vote again. I mean, those are quotes that's I'm not like making this up, you know what I mean? And and it was one of the I was like, what is he saying? How do you interpret that. Because that's like something again, I think it's like there was almost a code there, being being offered because, you know, he is very clear that he, that, that, that evangelical Christians put him over the top and he, you know, he and what he said to them even in 2016 was like, I'm the only one who's going to speak for you.

You're, you know, no one else cares about you, but they should care about you and the Christian, the Christian lobbying group and all of this kind of stuff. But then now again, he's trying to call on that. And what did you think he was saying when he said, well, I.

RANDALL BALMER:

I think everything about Donald Trump has to be interpreted through the lens of his own narcissism. And so I think what he was really saying is that give me a second term, then I'll be off the, you know, I'll, I'll fix everything for you. What? Whatever that means. But but you won't need to vote again because I'm not going to be on the ballot. That's all he cares about, you know? I mean, he doesn't talk about it. He doesn't care about a legacy. He just. It's all about him and his narcissism. But, you know, the statement itself was pretty, as you say, pretty jarring and and unfortunate, I think. But I think what he's what he's playing on and I think there's a part of his brilliance.

I don't think it's I don't think he realizes it, but he's kind of stumbled upon it. But, I think what he's playing on is this sense of victimization and evangelicals for and again, as, as I said earlier, I grew up in the subculture, so I know it very well. evangelicals have long considered themselves to be victims and to be marginal. And you're right, they no longer are in terms of their political power these days, they're not marginal at all. But you never they they sustain this rhetoric of victimization. And I think one of the reasons they were drawn to Donald Trump is that, frankly, he speaks to this rhetoric of victimization better than anyone I've ever heard. it's all about him. Of course, he's always the victim, but I think they they there was something in that vocabulary that that resonated with them. and I think that's one of the reasons that they were were drawn to him. So when he talks about fixing everything for for evangelicals, I mean, he's, you know, he's talking about Christian nationalism.

And we can talk more specifically about that. But but he's also appealing to their sense of being victimized somehow in, in the society. Again, it's utterly false. It's no less false, frankly, than the abortion myth in the 1970s. But it's a very effective rallying cry, right?

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Well, how do you define Christian nationalism?

RANDALL BALMER:

Well, as I understand it, it's, actually, I was asked this, yesterday in an interview, and I just came to me, and I think it's true. a Christian nationalism believes two out of the following three things. One, America was founded as a Christian nation. To America is a Christian nation or three. America should be a Christian nation. And I think Christian nationalism means believing in two out of those three, or at least two. And and some, I'm sure, believe all three. But I the shorthand definition, I think, is this notion that America is and perhaps always has been a Christian nation. And that, of course, is demonstrably false.

And it's a very, very dangerous ideology, it seems to me.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Yeah. Well, it's and, you know, not only is it false, you know, from a broader sense of democracy and also the Constitution, small things like that, but it's, it's very it's very interesting like what they mean by Christian. Yeah. You know, which is very like looking at made in their own image and like, you know, a commie like me or you It's definitely not what they mean by America. You know, it's very much their idea of who they are. And, you know, that's that's, I think, a really important, element because it's not only, you know, an affront to people of other faiths and, and, and people who, you know, adhere to no particular faith tradition, but are every bit as fully American as as anyone else. but also to the to the millions and millions of Christians who don't believe as they do. Right? You know what I mean? So, like the internal like, you know, the internal disconnect and is it, you know, is stunning and yet, you know, they they really do when they, they really believe that they also I mean, I think the one additional thing I would say is that they want to use the levers of government in order to enforce that vision.

And I, you know, and and that is, you know, that's that's the reason they're taking over school boards and they're taking over, you know, and you have the governor of, of, of Oklahoma declaring the whole state for Jesus. And then, of course, his school district attorney and leader, is now saying that, you know, the Bible has to be taught in schools. And so, like, it really is like not only saying it, but then enacting policies to enforce it in their own image. And that's and that's.

RANDALL BALMER:

And it's just, it's a, it's a grievous mistake. And, I think Christian nationalism is wrong for three reasons. The first is theological. What did Jesus say? My kingdom is not of this world. And the conversation's why even having this.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

And like the major temptation that he faced was the devil saying, I'll give it all to you. Oh, I'll give it all to you, you know, and, and and Jesus says, no, thank you.

It's one of the most important moments in the whole gospel is the devil says, I'll give you all the kingdoms. You can. You can control everything. And he's like, that's not the way it's going to go.

RANDALL BALMER:

I wrote a sermon recently for the lectionary at the end of July, and I'd never noticed this before, but in, in, John chapter six, between the story of the feeding of the 5000 and Jesus walking on the, Sea of Galilee, there's a single sentence that said that Jesus sensed. I'm paraphrasing. I don't have the wording in front of me. Jesus sensed that the crowd wanted to make him king, and so he retired to the wilderness. He did not want it.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Wow. Wow. That's. I know, that's very good.

RANDALL BALMER:

It's a single sentence and I.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Yeah, but that's an important sentence.

RANDALL BALMER:

Absolutey. Right. So no. So it's wrong on theological reasons. I mean it's dead wrong on in terms of history, you got these people out there.

David Barton is is the is the main, Right, right. I mean, I you know, it's wrong, but I mean, he's he's he's done untold damage with this, arguing that the founders were evangelical Christians. I mean, you know, you and I don't have to have that conversation. I mean, it's just so ridiculous as to be laughable. But people are believing this and people are eating it up. another bit of evidence, the Treaty of Tripoli. And I don't know if you know this. That's right. It was negotiated at the end of George Washington's administration, sent to the Senate for ratification by John Adams, read aloud before the Senate, and ratified unanimously by the US Senate on, I believe, July 7th 19, 1797. Don't call me to that date. I know it's 1797, But article 11 of the treaty says, and again, I'm paraphrasing because I don't have in front of me. But article 11 says the United States is not in any sense founded on the Christian religion.

I mean, that's pretty explicit. In the United States.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

That's like, I think what the Treaty of Tripoli is like, you know, when I have my, a keynote that that is the one where I literally before I mentioned, I said, has anybody heard of the Treaty of Tripoli? No one. No. That's right. And yeah. And yet, you know, the evidence of that is that unanimously the Senate, you know, endorsed it.

RANDALL BALMER:

It ratified. Yeah. Absolutely. Right. And and you have the First Amendment itself. And I have to say, Paul, I'm I'm worried I you know, I, I've taken to saying that I wish that our current Supreme Court had half of the deference toward the First Amendment, as it does to the Second Amendment right. The Supreme Court is steadily whittling away at this wall of separation between church and state. And let's remember where that came from.

The wall of separation that that metaphor originated with Roger Williams, who's the founder of the Baptist tradition in America. You and your people are Baptist, and you know this very well. I'm not saying you are Baptist today, but, you know, that's your business.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

So I am a Baptist. No, I'm American Baptist. Okay. That's a that's the ordination that I enjoy and have served. Yeah. Yeah.

RANDALL BALMER:

I didn't realize that. Yeah, I knew your grandfather was, but. Yes, but, that whole thing comes from Roger Williams. He writes a treatise in 1644, and he argues for separating the garden of the church from the wilderness of the world by means of a wall of separation. Now that's become so familiar that we kind of dismiss it, but let's remember the context. Roger Williams in the 17th century was not a member of the Sierra Club. That is to say, he didn't share our current romance toward wilderness or him. Wilderness was a place of danger where evil lurked. And when he talks about protecting the garden of the church from the wilderness of the world, his principal concern is to maintain the integrity of the faith, lest it be compromised by too close association with the state.

And we miss that. And that's very important. And I sometimes when I talk about this, sometimes I do a follow up and I talk about the fact that and and I don't know if he knew this and doesn't matter if you did or not, but I was one of the expert witnesses in the Alabama Ten Commandments case when the Chief Justice, Roy Moore, plopped this granite monument in the judicial building in Montgomery. And when Judge Thompson ruled correctly that the Ten Commandments in that space violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment and ordered that monument removed, one of the protesters screamed, get your hands off, my God! Now, you and I both know that one of those commandments on the side of the monument says something about graven images. And that, I think, was precisely was Roger Williams point about protecting the garden of the church from the wilderness of the world?

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Yeah. I mean, one of the things I think is so important, just to underscore and even in this conversation for our listeners, is that a lot of us who are so concerned with this, you know, so-called separation of church and state, I would argue that the Supreme Court has has done such damage to it that, in effect, it's no longer, you know, operational law.

But, you know, those of us who are arguing for this, these, these protections are not arguing it, actually. I mean, there's there are some secular people who argue it and legitimately so, but many of us are religious folks who actually see the danger, to religion in all of this. And, and we are often, you know, speaking up. I, I think one of the things I would love to, you know, touch on is, the most recent book you talked about because a lot of, a lot of your books have been like looking. Look at this, look at this. This is like, you know, we have to, you know, we have to be aware of what's happening. You know, the book, that I want to, you know, talk about is is the one that you wrote about saving faith. Yeah. And what does it mean to reclaim the prophetic voice? How do you you know, first of all, I think it's I'm not sure that I said it, but I think we should underscore it.

You're also a priest, an Episcopal priest. And, so you come at this, like, legitimately from trying to find, you know, a way that faith can still be a play, an important role in our world. say a little bit more about why you wrote that book and, and then like, and some of the lessons, for today, for those of us who continue to be within the religion space but are looking to do it well.

RANDALL BALMER:

Sure. Yeah. I wrote the book in part. I guess it was sort of a follow up to bad Faith. You know, saving faith. Bad faith. You know, the different publishers. But, because I was trying to to look at this Christian nationalism stuff. And by the way, I don't like the term Christian nationalism. I don't think there's anything Christian about it, frankly. So but that's what we're working with. So we'll we'll use the use of the phrase as it's popularly used these days. and try to understand the appeal of it.

And I think I began by saying, look, religion is in trouble in this country. I think, not in terms of numbers necessarily, although that's part of it. But you have the Catholic Church, of course, when still reeling, I think, from the pedophilia scandals as well as from the fact that the, the bishops, at least many of the prominent bishops are, are trumpists in these days. And, you know, talk about losing prophetic voice. I think that's a pretty good, good example of that. Mainline Protestantism, as both you and I know is is on the skids in many ways, although there are, the prophetic witness I think is still there, but it's not, not as robust as perhaps it once was. And then you have the evangelicals who are, have lost their soul, I think, to the religious right. And I'd be happy to talk more about that if you want to, and then try to understand what it is that that is so attractive about this Christian nationalism.

I think a big part of it is it appeals to nostalgia. And you and I both know that nostalgia is a slippery thing, and we can be nostalgic for things that never really were there. And I think that helps to explain some of the the 1950s nostalgia that we hear coming out of that quarter that is, you know, looking for a simpler time. And I talk about how many so-called pilgrims go to Mount Airy, North Carolina, every, every year, to which is, you know, the the kind of fictional birthplace of The Andy Griffith Show. And they say, you know, talk about the the values that once defined America. Well, did they ever. Yeah.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

That's a long and and of course, like, you know, according to who like if you're if you're if you're if you're vantage point was as a black American, you know, you know, and, and, and and that religious tradition, of course, had to, exercise a different kind of prophetic witness out of self-preservation and the protection of, of its people.

And, but going back, I just I just just wanted to note, you know, you're putting this juxtaposition. I don't know if you saw this image that actually Donald Trump himself tweeted, which was on one side, it was like this very, like picturesque, like, American flag America, you know, as we understand Americana. And on the other, it's like, you know, people like, you know, black people and immigrants. And it was like, which one? Which future do you want? And it's like, and it was just so Latently this nostalgia that you talking about leaning into it with? Explicit racial undertones or overtones. You know what I mean? And I just but I do think that what you're talking about, this nostalgia, when everyone was okay and it's like, yeah, the myth of nostalgia is so, like, rough and, and so I think you're. I don't mean to interrupt your flow, but I just am under underlining it. It feels like, really, really nefarious.

RANDALL BALMER:

It hit. No, it is. And then, you know, I go on to, to argue that, you know, if we are going to reclaim our prophetic voice, that is people of faith, I think we have to come to terms with our past, and much of that has to do with race. And we we're really done that. And yeah. you know, this is, you know, people historians talk about, about racism as, America's original sin. And I think it's a fairly good description. We haven't come to terms. And the fact that the religious right was born out of racism. There's no pretty way to say that, in defense of segregation. I think we have to come to terms with that if we're going to reclaim our prophetic voice, but also then finally just to, to to look at Jesus. Now, I grew up in a tradition, you know, I heard this, you know, I mean, I'm sure a million times, right? The word of God, the word of God, and you have the evangelists, you know, kind of riffling through the pages of his Bible and so forth.

But if you take John one seriously, as I do, Jesus is the Word of God, right? That's what John is all about. And that is to say that if we're going to reclaim our prophetic voice, we need to pay attention to Jesus in particular. No, it's not to say that the rest of the Bible is negligible. I'm not saying that for for a moment, but I think we need to focus on Jesus. And I'll just add an anecdote here, to say that, you know, we talked earlier, I, I'm, I value and I honor my evangelical upbringing and I still I still cling to that in many ways, even though I, I, I bristle these days of being called an evangelical because I know what people mean by that. It's not what I mean by that, but I know what they mean by that. But when I was growing up, most of the sermons I heard, admittedly, at the from my father, were sermons, based on the writings of Paul in the New Testament.

And I want to get back to and in my own preaching I preach from the Gospels almost, I would say, 98% of the time, because that's where we find Jesus, that's where we find the Word of God is looking at the life of Jesus. And I think we need to get back to that.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Well, I think, I think the headline that I'm going to tweet is Randall Balmer insists that Jesus is our. The only way that we can get that.

RANDALL BALMER:

I'm fine with that.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

You know, I mean, it's great, I think, but one of the funny, you know, the funny thing is, like, you know, there's anecdotes out of there, like, you know, someone reading the sermon on the Mount from Jesus. And he said, you know, all these things and someone saying, we need Karl Marx out of our church.

RANDALL BALMER:

And when did my pastor become a socialist?

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Yeah, exactly. Exactly. so, you know, one of the things I wanted to talk about a little bit more was, I'm just really interested in the governor of, of Minnesota, almost as someone who is from this mainline tradition, but and is actually very, you know, kind of participates in his Lutheran faith and what that has inspired in him.

And one of the, you know, I had a chance to talk to someone who has known them and has benefited someone who's Muslim, who in Nigeria said we had her on the on the show a couple of weeks ago, and she was just talking about how the the Lutheranism of the waltzes actually inspired this great commitment to interfaith, to looking at race, to looking at immigration, to looking at the way, you know, food operates and the scarcity of food. And and it was just really it was interesting coming from a muslim leader who, you know, and I think we, you know, this is something that I love, and I think we need as much of it as we can, who looked at someone else's faith and said, this is really important and people shouldn't gloss over it. Like it's really important that the role that faith has, you know, in his personal life, also like his LGBTQ commitment, his own church is very, involved in that. And so I just think it's I wonder if you have been following that at all as something, you know, that that that ties into your your hope that we might, you know, save faith.

RANDALL BALMER:

Yeah. Well, I like the rest of the nation or most of the rest of the nation. I'm just now getting to know Tim Walz a little bit. And I have to say, it's a lot.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

For me, too.

RANDALL BALMER:

Yeah. And, also add that, that I used to live in his congressional district in rural southern Minnesota. And believe me, it was rural. Yeah, my father was a pastor.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Is that where you're from? You're from Minnesota?

RANDALL BALMER:

Well, that was one of his postcards. East chain, Minnesota. East chain, Minnesota. Let's put it this way. It's a distant suburb of Fairmont Municipal.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Oh, wow. Oh, yeah. Okay. Yeah. Which was the big city.

RANDALL BALMER:

Yes, exactly. And and, you know, we we lived literally surrounded by cornfields. That's not a metaphor. that was that was really true. So I lived and I know that that area pretty well. So I'm just kind of getting to know him as myself. But I have to say that I think it's a delightful choice. And I think, learning more about his faith and the fact that it means something to him and the fact that, as you say, a Lutheran but also a football coach would take it upon himself to, be the advisor, I think it was to LGBT, community. And trying to defend them, I think is really quite remarkable.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Really amazing.

RANDALL BALMER:

And I think it's important it's important that Americans understand that the faith or Protestant faith or Christian faith, is not, is not synonymous with the religious right.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Interfaith Alliance, we're constantly like, just reminding people the majority of religious folks actually support LGBTQ equality. Exactly. The majority of religious folks actually support a, you know, reproductive right to reproductive freedom.

However that's exercised, with, with, and other issues like this, these are not outlier issues for religious folks, but the, the narrative has been so strongly influenced that it's, you know, Christians versus like these, you know, you know, LGBTQ community. It's just not the truth. And this is like, this is what why scholarship is so important. And and then not only scholarship, but figuring out ways to really impact the, the public understanding. So I mean, that's the reason your, your public work has been so helpful is that you you are, you know, by any standards, a great scholar, but that your scholarship, you know, kind of enters into our public awareness is what really has been helpful. And I do think, like, you know, this is a time when we're going to need really smart people talking about religion and democracy and, you know, our interfaith alliances, tagline that we just, you know, we just did a kind of a brand refresh, but we have a new tagline saying Achieving Democracy together because we really view religion as one of the building blocks that can be a productive, positive part of the democracy project.

How do you understand religion and democracy?

RANDALL BALMER:

It's a question I don't think I've ever had before. I think. I think religion certainly contributes to democracy. And some people have misinterpreted what I said, what what I have said over the years and including my my Dogged defense of the First Amendment, which I believe is America's best idea. I think a First Amendment is America's best idea, in fact. I'm I'm working on a book with that title because I think it's so important. But people have misinterpreted me to say that that voices of faith should not be part of our political discourse. And I couldn't disagree more strongly. I think people have every right to bring their religious or faith commitments into the arena of public discourse, and I think public discourse will be impoverished without those voices. But what I think we also have to observe is what Jeffrey Stout calls the traditions of democracy. That is to say that over the last 200 plus years, certain protocols have emerged with as we Americans begin to understand what it means to be a democratic place, obviously a lowercase d here.

And one of those traditions is that no one voice dominates that arena of political discourse. That is to say, I have every right to express my my religiously informed convictions in the arena of public discourse. But I also have an obligation to listen to others as well. Right? And that is what's missing in this whole nonsense, and I'll call it that of Christian nationalism. Right. They only their voices to be expressed in the arena of public discourse or in the laws, depending on who we're talking about. But the the protocols of democracy expect, if not demand, that we listen to other voices as well as well. And that, I think, is the richness, the texture of American life.