State of Belief

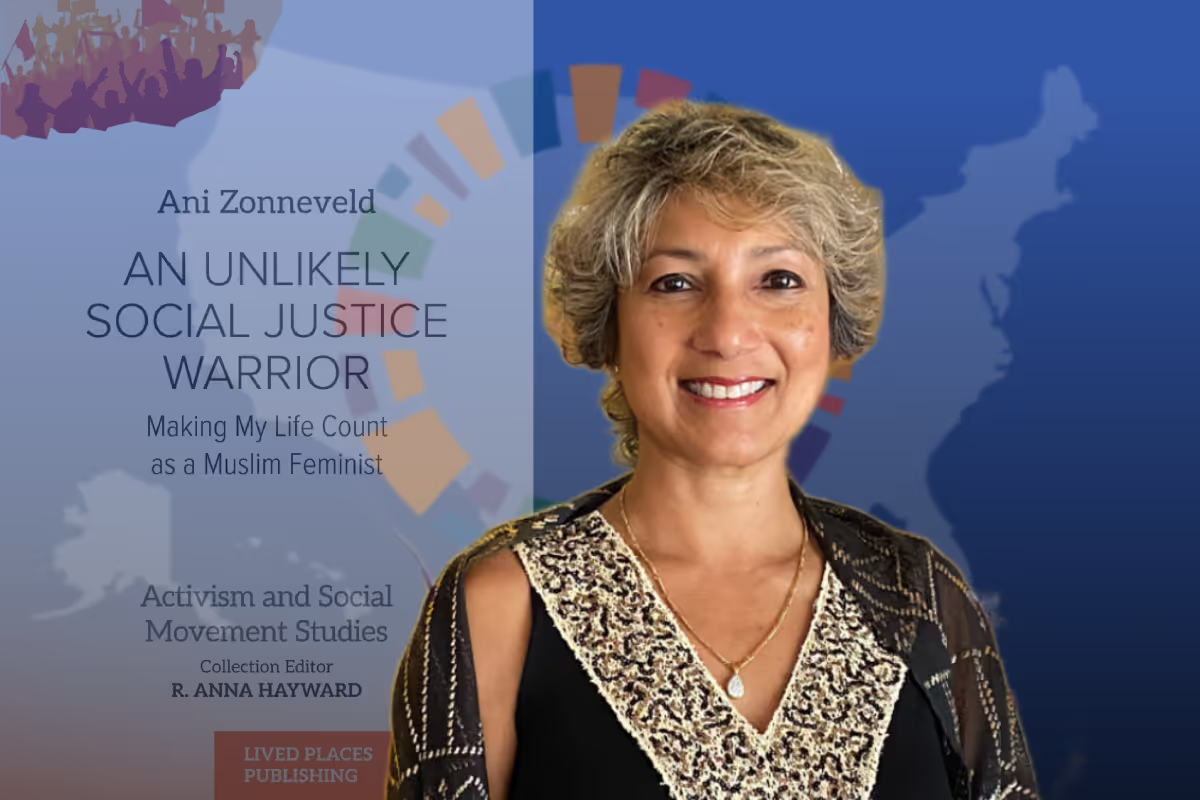

An Unlikely Social Justice Warrior: Muslim Feminist Ani Zonneveld

This week on The State of Belief, host Rev. Paul Brandeis Raushenbush sits down with Ani Zonneveld, feminist Muslim activist, musician, and Grammy-winning songwriter. Ani’s journey from Malaysia to Germany, Egypt, India and eventually Los Angeles - and the lessons learned along the way - is nothing short of inspiring. And she lays it all out in her brand-new memoir, titled The Unlikely Social Justice Warrior: Making My Life Count as a Muslim Feminist.

As a diplomat’s daughter, Ani nurtured her social justice consciousness despite a privileged upbringing. From witnessing the aftermath of the Sinai War to playing soccer with a Dalit child in India, these moments shaped her anti-war and anti-racist beliefs.

It was after 9/11 that Ani delved deep into Islam, discovering its egalitarian and inclusive roots and founding Muslims for Progressive Values, championing LGBTQ+ inclusion, gender equality, and human rights from a faith-based perspective.

Music is a cornerstone of Ani’s spiritual journey. While pursuing a professional music career in LA, she faced sexism and racism, and experienced suppression of the diverse musical heritage of Muslim immigrants in the American context. Ani sees a conservative swing in Islam, which she describes as quite different from the religious tradition she grew up in.

Ani hopes to inspire young people to channel their anger constructively and build alliances across differences, based on being exposed as students to diverse cultures and traditions in public schools, countering conservative efforts to restrict such content.

There’s a lot of value in this conversation. I hope you’ll share it with someone you know who’ll enjoy hearing it!

Transcript

REV. PAUL BRANDEIS RAUSHENBUSH, HOST:

Ani Zonneveld is a multi-talented Malaysian-born musician, Grammy-winning songwriter, and passionate activist, who has forged a unique path blending art, faith, and social justice. As the daughter of a diplomat, she was raised at posts in Germany, Egypt and India. After 9/11, Ani turned from a successful music career to confront the growing hate- and fear-filled narratives around Islam. Of course, her inclusive feminist values didn't align with every Muslim community, either. All of which led her to found Muslims for Progressive Values in 2007, an international organization championing LGBTQ+inclusion, gender equality, interfaith marriage, and human rights from a faith-based perspective.

Ani's fascinating new memoir is titled The Unlikely Social Justice Warrior: Making My Life Count as a Muslim Feminist,and I am thrilled that it brings her to The State of Belief.

Ani, welcome!

ANI ZONNEVELD:

Hi, Paul, thanks for having me.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

You and I actually go pretty far back. I remember when I first started at Huffington Post, which was literally decades ago, we can start saying - yeah, it's weird when your life allows you to start saying decades ago, but a really a long time ago - and you had started this great organization, Muslims for Progressive Values. And I remember us having conversations and you being part of the Huffington Post world and featuring your work. Great religion reporter. So this is not Johnny-come-lately work for you.

ANI ZONNEVELD:

Yeah, and I had a column on Huffington Post.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

So with that opener, our listeners can feel that we've actually been working alongside one another for a while. Can you take us back? You have a really fascinating history, and we're so glad that people are going to be able to appreciate it. The Unlikely Social Justice Warrior: Making My Life Count as a Muslim Feminist. Why unlikely?

ANI ZONNEVELD:

Because I was raised so privileged as a diplomat's daughter. But the privilege was not just in the status, but the privilege, in my opinion, is the way I was raised. And that is, my parents made sure that I was very conscientious of social issues. And so even though we were pampered, they made sure that we had these educational excursions where we saw how others suffered because of politics and economics, for example.

And the unlikely part is that my upbringing is what anchored me in my values, anchors me and my values. But the unlikely part is because I live in Los Angeles; I was in the music business and I live here in LA. And so I'm privileged. I don't have to do this work. I'm good, right?But my social justice conscience and the way I was raised, that there's no way I can just turn a blind eye to a lot of what's going on in our society. So that's why that “unlikely” is…

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Right. And so just getting a little bit more into your background. I think sometimes when you write a book like that, somethings start showing up that you're like, oh, right. I'm remembering that. I remember that moment with my family, or I remember that.

And all of a sudden there seems to be moments that are more laden with meaning. What are some of the moments that you can remember? You mentioned being exposed to things that your family made sure you were aware of. Can you think of particular moments that stood out to you that you wanted to make sure to include in your memoir?

ANI ZONNEVELD:

Yes. So here in Los Angeles, for example, a few years ago, we partnered with Hindus for Human Rights and other faith-based organizations. And we realized that the Dalits - the untouchables in the caste system - were being discriminated in the workspace by Hindus of the higher castes in the tech industry. And so we had lobbied to get the word “caste”included in the discrimination categories in California law. And for me - I'm not a Dalit, I'm not a Hindu, I’m a Muslim - but it really resonated for me,because when I was in India, living in India, I used to have my soccer drills with the gardener’s son, and they were Dalits.

And my mom came up to me and said, hey, honey,you know, I just want you to know that some folks are talking behind your back about how as an ambassador’s daughter you shouldn't be playing soccer with the child of a Dalit, who's a Dalit. And I'm like, so, you know, who cares? And my mom said, no, I'm just telling you how society is. Just carry on with what you'redoing. So so that's some of the example.

And there are other examples about the caste system that I also write about - I'm writing about in a very visual way to express that we were, even as a child, were actively anti-racist. We didn't know that; we didn't have that academic term. But that's how we lived our lives.So that's one example.

Another example is that when I was about 12 years old, we lived in Cairo. And my dad made arrangements with the Egyptian military escort to go and visit Portside City, which was right by Sinai and the Sinai Peninsula. And it was right after the Sinai War with Israel.

And so he took us there just to, like, this is what war looks like, kids, you know. And so I see bombed homes and apartment buildings sliced, and you can see people's personal belongings and you can hear land mines being detonated by the military and all of that. And so for me, I described that from a young age, how it is I hate war. And so I'm very anti-war. I can't watch violence on television. It just makes my stomach turn.So those are some of the upbringing that has really affected the way I work and think. And yeah, my belief system.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

And you know, I think the term for being a Muslim and also being LGBTQ-inclusive, you and I know that that's not that uncommon. You and I know that out there, that's actually - I don't have the exact statistics,but this is not an uncommon thing. But there's a narrative out there that those two things can't go together. How did that become part of your sense of calling and what you were trying to create with Muslims for Progressive Values, but also in your own life?

ANI ZONNEVELD:

Well, before I get into that, I just want to acknowledge my heart goes out to the family of Imam Ali, who was the first openly gay imam, who passed away last Sunday. so we're really sad about it,because obviously he was very much involved in Muslims for Progressive Values,and contributed a lot to the progressive theology, one that is inclusive of LGBT Muslims.

For me, after 9/11, when I decided to relearn Islam for myself - because this whole jihad thing, I was like, what the hell is this thing? I'm born raised Muslim; I've never heard of killing innocent people by way of suicide. I mean, it's such a double whammy. It's crazy.

So I decided, well, okay, do I still want to be a Muslim? And it was, so why? And if not, why? Why? I had to have my reasons.And so, as I was relearning this for myself, I realized that it was actually really more egalitarian than even how I was raised, and more inclusive and all these wonderful things that were erased or not taught to us. You know,obviously, patriarchy had its reasons, right? So it's a constant theme, this patriarchal and all these traditions. So when I was at that point I was like,well, if it's so egalitarian and inclusive and if there's a Spirit of God in all of us, regardless of whether you're Muslim or not, whether you're straight or gay or trans or what have you, then why are we discriminating on the basis of religion, sex, gender identity, what have you.

So for me, if I really, truly want to practice a real Islam, I need to shed any iota of discrimination, of this superiority over another. Not that I had anyway, because that's not how I was raised, so it was easier for me. It was easy for me to embrace this inclusive and loving Islam. That's number one.

And number two - I also write about this in my book - I had an uncle that lived with us throughout the 16 years plus that we lived abroad. And he was my mother's brother and he was our chef. And so he would cook for us, and he was always feminine. And I didn't know he was gay.And so many decades later, I went to my oldest brother and I asked him straight up, hey, was Uncle Bakar gay? And he was like, you know, big wide smile said,yeah, he was gay. And then it kind of made sense.

A lot of things started making sense after that. And so I was raised around my gay uncle not knowing he was gay. And I also realize now that there was that invisible wall between us and I now understand why.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Well, isn't it amazing. But you know what? You must have been able to pick up - because your family had him close - you must have been able to pick up the kind of respect. And maybe you weren't around as much casual denigration of LGBTQ people that sometimes, you know, people who don't think about it. But because your uncle was there, maybe they were less likely to do it. And I'm sure your mom must have known at the time.

ANI ZONNEVELD:

And probably it's also like, denying it, or don't ask, don't tell. But I think, also, he was probably brought along with us for the 16 plus years as a way to give him something that was meaningful in his life, because he probably needed it, right? So, you know, I don't actually talk to my mom about these things because she doesn't really like what I'm doing…

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Oh! Say more about that. I mean, because once you start being public and, putting all of this into practice and try to talk about this in a more public way, there are people who are saying, what are you doing? Keep quiet. So that must have been part of your journey in this whole effort.

ANI ZONNEVELD:

Yeah. And the thing about it that was strange is, I am the product of the way my parents raised me. And that is inclusive, a nondiscriminating worldview. I mean, they have never uttered any hate towards anyone. I've never heard them say anything negative about a group of people, a nationality,ethnicity, what have you. But you know, our Muslim societies have changed, and since the 80s, it's become very Wahhabi. It's become so draconian and very intolerant in its teachings. And the Islam I was raised on is very different from the Islam of today.

And so, my mom has become more - I don't callit orthodox because it's not orthodox - it's what I call a more twisted, a patriarchal, tribal interpretation of Islam, based on the Wahhabis and the influence of Saudi Arabia, which now obviously has changed by 80 degrees. But,you know, the impact on Muslim societies will linger on for another generation,at least. And that's what I would say: the Saudi colonialism of their Islamic culture on Muslim societies. Now, we don't talk in that term because we say colonialism as that White man thing. But no, we were colonized culturally by the Saudi version of Islam -not just Malaysia, but the vast Muslim societies. So that's been the influence.

And then my sister is also a graduate of Al-Azhar University, and she studied Sharia law. And so coming from that school of thought, it's very rigid and it's orthodoxy intolerant. And so that has been the influence, in addition to cultural influence, that's been the the theological influence in my family. So my family has shifted to the right, and I have shifted to a more egalitarian worldview. I stayed in the egalitarian worldview, let's put it that way.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

But I think the way you can tell it is that you stayed true to the way you were raised. The Islam in which you were raised. It's been interesting. This is not in any way an endorsement, but I live in New York City, and the mayoral race has been interesting, with a Muslim candidate. And it's been kind of amazing to watch him navigate the identity as a Muslim, but then talking about trans rights, talking about a full egalitarian worldview. And I think that's very confusing for some people who want to actually pin something on him. and that it's confusing to Muslims and non-Muslims alike, who are used to being able to understand theplaybook of Islam in America, right? And he's bringing some really interesting things.

And I think how he and Brad Lander have been creating coalition, and there was just an amazing video of both of them in the in the Pride parade with flags and dancing around and having a blast and being unapologetic for everything that they are. And I just think that that's what I meant by there's a lot of Muslims out there.

One, there's a lot of LGBTQ Muslims. People think even in Christianity they're like, well, you can't be Christian and gay.I'm just like, well, I mean, look around. But also, I'm wondering if you have noticed that navigation. And also is there something generational that, that you've recognized over the years. I'm curious how you're sensing how your message is landing today in America, especially in this moment, with the MAGA effort at domination.

ANI ZONNEVELD:

Yeah. Now, well, according to Pew, they did a study. They were doing a study of American Muslims over the span of ten years.They asked the same questions in 2007, 2013 and 2017. And on the issue of LGBT rights, it went in favor of LGBTQ rights over the ten year span, from 27% to 52% in favor of LGBTQ rights.

And these are Muslims that they interviewed who identified as Muslims, who were mosque-goers. so was very interesting. But obviously, now the numbers are much higher - and it is also generational. So you talk about Mamdani, but let me give you a little bit of - and I write about this extensively, I have a chapter on LGBTQ rights, even. And it is really about putting the spotlight on the hypocrisy of the Muslim religious leaders in America and how, when Trump won, when Trump, the first time around, was in power,was in office, the conservative Muslim mosques and leaders started redefining themselves as progressive. And so they started using the human rights language.We are egalitarian. We support LGBTQ rights. We support women's rights. It's all just a cover so that the progressive left would come to their defense and protect them. And, you know, paint over the walls that were spray painted with ugly messages that just really stuck up from Muslim rights during Trump I.

You had the Muslim ban - and I received my share of threats from the Trump fans. So then it was Biden. During Biden's term,midway, they decided to do a 180 degree pivot and say, oh, we apologize. We have sinned. You know, it's wrong to be gay and Muslim. And they did this whole position statement that was really so ugly. And because they felt safe to come out and come back into their true homophobic stance. I'm talking about, like,150 Muslim religious leaders - or claim to be leaders and claim, also, to have the authority to speak for all Muslims, which is bogus. So that was in 2023.And then when that statement came out, the political right, the Christian right took notice of, oh, we've got allies here. So then they started courting the Muslim right. So I define them as a Muslim right.

And then October 7th happened and then all these end time Islamophobic statements came popping back up. And then I was saying,oh, I guess this reminded the Muslim right about how Islamophobic the Christian right and the political right is. Hopefully that'll be the end to that relationship.

But then came 2024. They started courting the Muslim right aggressively. And obviously they won some of them over. And some of the imams advocated for the congregants to vote for Trump on the basis of supporting Palestine, supposedly. Because of the issue with Gaza. So that's kind of like the the whiplash of the Muslim right. You know, it's not principled. It's just hypocrisy.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

And, you know, you're absolutely right that the Christian right, especially the Christian right legal movement said, Oh, okay.It's one thing if we bring something, let's get the Muslims to bring it, for instance. And, Mahmoud. You know, that would have landed different had it been the Christian right. But Muslims, you know, one of the things we were trying to say with Mahmoud v. Taylor, which was the case where Muslim families were encouraged, frankly, by right wing Christian legal organizations,to file a complaint about being exposed at all to LGBTQ stories. They weren't pro-LGBTQ stories. They just were stories that had LGBTQ people in them,normalizing the existence of LGBTQ people.

And the day of oral arguments, I stood up with Maggie Siddiqi, who you may know, and we just both said, this is not an either-or.I was like, you know, as a gay parent, I want my kids to know about Islam. I want them to know that there's being studied side by side with Muslims. We can be together. And you don't have to agree with everything that everybody else...But we are in a democracy where we hopefully can. And so anyway, it's heartbreaking to see that alliance. It's like the interfaith of the right.

ANI ZONNEVELD:

So there is the multiracial right. It's the multiracial, political right, because it's not just Muslims; it's also Hindus, you know, the Hindutva, etc., etc. And there's also the Israeli lobbyists and the Zionists and the Christian right. So that's one camp. But I have to say before the Christian law firms really encouraging the Muslims, it really started in Maryland. And so we were talking to the chair of the Montgomery County, the council chair, about how to address this, because it popped up on my radar and people were calling me, how do we address this without seemingly being anti-Muslim and so on and so forth.

And then the one thing that was also shared with me were WhatsApp messages in these groups about how CAIR was saying, oh,we're going to take this all the way to the Supreme Court, when they lost the the case in Maryland itself. And, you know, folks need to understand the reason why we have the Muslim girl with the hijab dancing with her friends. This is in the Maryland public school curriculum. The reason why we have Pride puppy. It's because gay kids were being bullied. It's because Muslim kids were being bullied after 9/11. We don't want any of that. So we should really been couraging each other. You know, being exposed to each other's cultures and traditions and so on with no prejudice. And if we can't have that in the public school system, then what the hell? I mean, go to your Christian school, go to your Muslim school. Leave the rest of us alone.

So I wrote an op-ed on for Religion News Service about this, and I said, this is a terrible - if we lose this case - is a terrible precedent. And what they also did was even though the case at the Supreme Court was called Mahmoud vs. Taylor, they also included some Christian families and Jewish families to win over the Supreme Court judges. But the thing about it is that this is a slippery slope because, you know, there could be a group of parents, like, you know what? We don't want pictures of Black kids in our, you know, teaching about that. Or any subject matter.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Or Muslim, you know, Muslim that offends our,like, Christian background. We would rather not have our kids exposed to this religion. It's like, oh, okay. So we're going to stop having any acknowledgement of the diversity of America in our public schools. It's really a slippery slope is exactly right. It's terrible. And what a teacher is supposed to do.

ANI ZONNEVELD:

And our society in America is so segmented already thanks to the media and the channels and what things that are filtered for us. The only thing left was our public schools’ curriculum.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

It's part of a movement, as you know, because we have the public schools and then we also have the libraries; and the libraries are also getting attacked - and by the way, Muslim stories, there's people who are just like, get those out of there. So we have to be very careful. You know, of course, LGBT, Black stories, all of those are the first challenge. Muslims are not far behind. And Jewish stories, too. So it is a slippery slope.

ANI ZONNEVELD:

You know, what I found most hypocritical is that these Muslim families and everyone backing them up had an issue with LGBT stories, but did not have an issue with Muslim stories. I mean, how hypocritical is that?

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Exactly. And when I stood with Maggie in front of the Supreme Court, I was just like, I want to hear stories. We want to hear each other's stories, and that's all we have.

But speaking of stories, I want to turn to something that we haven't talked about yet. Let's talk about music. Can we talk about music and how music is part of your life? Because music, for me, was the way, frankly, that I became a minister. It's been my avenue to the divine. So much of my life has been about music, and I have to say, until I saw this book,I was like, she's a Grammy winner. What? Tell me about how music first appeared in your life and the role it continues to play in undergirding everything you do.

ANI ZONNEVELD:

Thank you. I was exposed to music as long as I can remember, so that's a long time. And my dad was the DJ of the house, believe it or not. You know, he was a strict dad six days out of the week, and then came Sunday. He was Mr. DJ in his sarong and his white singlet. And you know, I would be immersed in all kinds of music: opera, traditional Malay music,nationalistic songs from Malaysia because we just had our independence. And my dad played a role in that, you know? So I was really raised with that in my blood.And so there's obviously the Jacksons, the Osmonds, Petula Clark, Louis Armstrong. The whole spectrum.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

That's so instructive. Like, there's not one place it goes to. All we've been talking about, frankly, that there's something to gain from so many places. Why not yourself?

ANI ZONNEVELD:

Exactly. So that was my dad. And so I give him credit for that. And the thing about it is that I realized that when I was listening to music, and then when I bought my own 45, you know - I don't know if you remember that. So I would spin my own 45 or whatever was my favorite record, and I would listen to it over and like 50 times, just that one song.And I would listen to all the arrangement, all the production, not so much on the lyrics, but the melody and how the melody was arranged or the music was arranged around the melody, you know, etc. so I paid a lot of attention to that from a young age.

And then at five years old, my parents put me in piano classes. So I've been classically trained since I was five. And my mom would always say to my dad, if we're traveling somewhere and then all of a sudden, you know, you can't find Ani - just look for the closest music store.And that's where she's at, the record store. That's where we'll find her. So that's kind of my reputation. And so music was very consequential in my life.

And then after I graduated from college in Illinois, I studied economics and political science, I kept my promise to my parents. So then I said to that, okay, I kept my promise. And I want to do what I want to do. I want to do music. I'm moving to LA instead of going back to Malaysia and joining the Foreign Service. So my parents, okay, you know, you're on your own. Good luck.

So I struggled. Obviously, I didn't know anyone in the industry. I didn't really understand how the industry worked. I don't know how it works, still, and I was a real fish out of water because in the diplomatic and how I was raised, we had etiquette, we had protocol, we had manners.

In the music business. Oh my God. It was like dog-eat-dog world. I hate the industry. I just love music. I hate the industry.But fortunately for me, I started working with some really awesome people. And I was also doing more of the production work, the arrangements. I was doing more of what they call the guy thing. You know, girls were supposed to do the lyrics and melody and sing, and guys were doing all the production and the arrangement and the tech stuff, which was where I was doing.

So I didn't fit in in that way, as well. So it was a very sexist industry, very racist industry at that time. Probably not as much now. And then you had the different cliques: you had the Jewish group, you had the Black group, you had Latino, you had the Asian group. But I was not that kind of Asian. I was Southeast Asia, not Korean origin. You know, I just didn't fit in, so I was excluded. And discriminated and yeah, I had a really hard time.

But I started working with some amazing people.And Keb Mo, this contemporary blues artist, was a friend of mine for a longtime. And when he made it big, he pulled me in on projects. And so when you contribute a song on a project that wins a Grammy, then you become a Grammy-certified songwriter. So you get a certification, you don't get that trophy. So just to clarify.

And to stay on the theme of music, with Muslims for Progressive Values, one thing that's really void in American society, Muslim society, is music. In our faith tradition and from wherever we came from, from Malaysia, women sang and we had spiritual songs. Same in the Arab world. Turkey. Sufi. Everyone.Everyone from where we came from always had a music tradition in our Islamic culture. Somehow we've lost it all when we came to the United States. So it's been stripped off of all its fun stuff. And so whatever is musical is in the tradition and in the language of wherever we came from. And so now, over the years, I've created a catalog of Islamic spiritual songs, in English, as a way to create an American Muslim tradition.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Well, it is incredible. My husband wrote a book on Rumi. and so for seven years there was a lot of travel, including to Syria and Turkey. And I remember, just, the music was so important. And you would hear just incredible music. And I remember we were going to Damascus. We were driving in this big sun, and I'm going to mispronounce her name, but Khartoum Alum, it was an Egyptian singer.

ANI ZONNEVELD:

Umm Kulthum.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

She was, I mean, like 20 times the Beatles. I mean, people absolutely lost their minds when she would sing - and for good reason. And it is so important that we not strip our religious traditions. And I'm not singling out, I think that there's an impulse among some folks who want to be pure that the first to go, one, are women voices, and two, musical voices. And all the culture that surrounded the beautiful parts of the culture.And so I'm really feeling what you're saying, and I think we miss so much when we strip these voices that elevate us. I mean, you can't talk about spirituality without talking about music. I'm sorry.

ANI ZONNEVELD:

I completely agree. And so let me share one story. One of the impetus for starting Muslims for Progressive Values for me was because, after 9/11, I had written and produced an Islamic pop CD. And being from Malaysia, which is a Muslim-majority culture, it's like music, women singing. There's nothing taboo about it. And then, lo and behold, I had no idea what I was wading into here in the United States, that none of the Muslim retail stores would sell my CD because I was a female singer, number one. And number two, because I used all the musical instrumentation. And supposedly that is forbidden because Prophet Muhammad only had the percussion. And I'm like,what the hell is this? So I'm like, okay, I'm done with you guys. I left the mosque. And that's how MPV… That was one of those, you know, like, my anger.How dare you censor, you know, the female voice? that was number one.

And number two is that God is the most - this is my philosophy - God is the most creative entity. Period. And upon creating us as human beings, it’s the Spirit of God blown into the womb. So we all have that creative spirit in us. There's nothing more creative than singing and your voice and that spiritual connection with music through that singing voice.That's why we have the Azaan, the call for prayer, and the recitation in the Quran. When I do the recitation in Arabic, there's something in me that wakes up, right? So to really censor that is what we would say is to harden the human heart.

And when you harden the human heart is when the control, the patriarchy, misogynistic, the homophobic, all this dogma takes over - because you have lost that empathy and the compassion which is in your heart. And that's why every opening of the Quran except for one is “Bismillah Rahim,” in the name of God, the most compassionate, the most merciful. And the word “Rahim” in Arabic means “womb,” which is the most nurturing, the most protective, and the most compassionate space for any human being, or any animal for that matter. So that's the definition of God.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

And inherently female.

ANI ZONNEVELD:

Lo and behold, and yet we call God a “he.”Seriously.

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

Right. the book is The Unlikely Social Justice Warrior: Making My Life Count as a Muslim Feminist. I'm feeling like you're less and less unlikely all the time. The longer I listen to you, it feels like you're very, very likely. How would you like people to engage this book? It feels like some will be Muslims who are looking for this kind of testimony, this kind of voice to give them their own sense of agency. Others will be non-Muslims who would love to hear this kind of voice, also, because all traditions, by the way, are wrestling with patriarchy. There's not one that doesn't. But how do you imagine people interacting with your book?

ANI ZONNEVELD:

I am looking at this from the perspective of social justice and human rights. So it doesn't matter whether you're a person of faith, Muslim or not, or even secular or atheists, because there is value in utilizing a rights affirming language in advancing our common cause, you know, our common good. And so I really link a lot of stories in the book. So it's not linear. So I really go back and forth. You know, I'm talking about colonialism in Malaysia and comparing it to my experience in Burundi and how the people there were treated by the Belgians. So I really connect a lot of dots.

But most importantly, I think that it's important for people, for especially the young folks, because the publisher is focused on distributing in universities and colleges and there's questions at the end of the book about what exercises to do in order for you to learn better about certain subject matters. But I really want the younger folks to really have a long term strategy that anger is good, but use your anger in a constructive way and not in a destructive way, and also to use your anger to fuel longevity, to fuel sustainability, your advocacy in a long term goal. Not this, you know, chop everybody's knees off, and to look at the world from the prism of, you need to go where people are at and you need to win people over.And that's hard to do when you're super angry and when you hate another group.

And we're having this problem, also, within the progressive groups, whether Muslim or not, when it comes to what Israel is doing to the Palestinians. And there's this, you know, blanket statement about Israel in general and so on and so forth. But there are Israelis who are fighting the cause from within. And so we have to work with groups of people who share our values, regardless of what they are. and so that's where I'm hoping that people will get: well, what is the common denominator, that thread that binds you to a particular person that you otherwise do not agree with. And how do you bring them along? How do you bring others along, based on that shared sliver of shared values?

PAUL RAUSHENBUSH:

I think that is a great message for right now,because as you know, we're never going to get to the total purity of everyone agreeing on everything. There’s no such thing.

This idea of values. And can we work together on on certain things? Can we come together? And I think the big movements that have been successful have really tried to incorporate as many people as possible to come together and recognize that we're not exactly on the same page,sometimes, but but if we're willing to show up with one another, and if we're willing to move forward with one another, that can be courage. And so I just really appreciate that as a theme.

I think this is such an important book. I think it allows people to maybe see themselves in a in a narrative that they thought,Oh, I'm so weird. No one is possibly like me. Well, you know what? Actually,there's a lot of us weirdos out there, who are inspired by music and inspired by all kinds of different ways of coming together and who have had life experiences that opened us up. You know, I don't think we're not doing like the Keep Austin Weird kind of thing, but the idea of, can we find one another andbe with one another?

I think it's just a beautiful book. The Unlikely Social Justice Warrior: Making My Life Count as a Muslim Feminist,I just love this memoir. I love the fact that you're writing it now, after all these years of working so hard. And I just want to thank you so much for joining me on The State of Belief, and for all of our listeners I say, thank you.

ANI ZONNEVELD:

Thank you, Paul. Thank you.

Jewish-Muslim Solidarity: Moral Witness in Pressing Times

Highlights from a Capitol Hill briefing on Jewish-Muslim solidarity as a defense against authoritarianism, featuring prominent Muslim and Jewish leaders and lawmakers. With discussion and inspiration from host Rev. Paul Brandeis Raushenbush and interfaith organizer Maggie Siddiqi.

We The People v Trump with Democracy Forward's Skye Perryman

Host Paul Brandeis Raushenbush talks with Democracy Forward President and CEO Skye Perryman about the first year of the second Trump administration. Skye describes how, amid a flood of policies and orders emanating from the White House, Democracy Forward's attorneys have brought many hundreds of challenges in court - and have prevailed in a great majority of them.

Courage in Community: Minnesota Faith Leaders Respond to ICE Crisis

Host Rev. Paul Brandeis Raushenbush talks with four Minnesota faith leaders on the ground defending their communities against ICE attacks: Rev. Susie Hayward, Rev. Dr. Rebecca Voelkel, Rev. Jim Bear Jacobs, and Rev. Dr. Jia Starr Brown.